Category Archives: Democracy

How New Digital Technology Encourages Terrorism and Threatens Democracy

There was a time when surveillance and security concerns did not trample on the rights of individuals or democratic principles because the entire matter was too difficult and cumbersome. In the old days when the threat was only ideological (e.g. communism) security issues were far less immediate and gathering information was a slow and lumbering process. But now there is a marriage of violence and digital technology. It is no accident that the correlation between terrorism and media presence and sophistication is strong and positive. As digital technology has advanced, along with the ease and availability of violence, so has terrorist activity and the technology and security requirements necessary to control it.

There was a time when surveillance and security concerns did not trample on the rights of individuals or democratic principles because the entire matter was too difficult and cumbersome. In the old days when the threat was only ideological (e.g. communism) security issues were far less immediate and gathering information was a slow and lumbering process. But now there is a marriage of violence and digital technology. It is no accident that the correlation between terrorism and media presence and sophistication is strong and positive. As digital technology has advanced, along with the ease and availability of violence, so has terrorist activity and the technology and security requirements necessary to control it.

The threat to individual rights and democratic processes is always easy to defend when faced with rank violence. Of course we cannot let extremist ideologies and easy violent behavior dictates the political environment. But digital technology allows nonstate actors as well as other participants to engage in violence with ease by historical standards. Again, during the relatively simple period of security issues during the Cold War if an individual were a potential threat to the United States he could be detained or we could even enlist the help of others and subject the individual to legal processes. In the modern digital age the means and techniques of interrogating individuals and gathering information are less compatible with legal principles and offer more options – some of them unpleasant and questionable legally and morally.

In the Cold War if we wanted to learn secrets about somebody someone could be assigned to “tail them” and see what they could learn. This was slow, unreliable, and not a very productive use of resources. It was impossible to have enough people assigned to potential sources of information. Searching your person or your property required legal permission. New digital media can gather vast amounts of information from your cell phone, websites, credit card purchases, etc. The state has the legal right to gather information from organizations and it can all be done by a few people in a single place. Moreover, all of the electronic data about you is potentially more informative and revealing than any information obtainable from a coworker or close friend. Purely human information is fallible; people are not paying attention to what you’re doing, or you forget what you did at a certain time and place. But your cell phone and computer don’t forget. It’s all there in simple searchable form.

In the Cold War there was no technology available for massive data-gathering like collecting phone messages from entire communities. Today, the technology is available along with the software sophistication for massive meta-data collection. In fact, Facebook does the equivalent every day.

The security issues in the modern era are serious because of the easy availability of violence and technology. The security sector of the state measures itself by its ability to prevent incidents and is thus motivated to do more and more, regardless of how far the edges of acceptability are pushed, to ensure that there are no more 9/11s. These conditions threaten our democracy as they push the pendulum more towards the security side of the continuum. Still, surveillance and security are part of any state and targeting an opponent of the state capable of violence is legitimate.

Practical limits and approval from proper chains of authority are the only answer to maintain the balance between security and democracy. But new challenges and interesting questions still are on the horizon. Google and Apple, for example, are planning on encryption devices in new versions of cell phones. Security forces are legitimately concerned that this will make important information even more difficult to obtain. But such devices will strike a blow for privacy and individual rights while maintaining the tension between security and democracy.

Educating for Free and Deliberative Speech

Hearing criticisms of your own convictions and learning the beliefs of others are training for life in the multi-faith society. Preventing open debate means that all believers, including atheists, remain in the prison of unconsidered opinion. The right to be offended, which is the other side of free speech, is therefore a genuine right. True belief and honest doubt are both impossible without it. John O’Sullivan

I have been a pretty standard liberal Democrat all my life, but recently I have been more critical of the left’s retreat from First Amendment protections. I’m talking about the left’s willingness to restrict symbolic expression that is critical of an ethnopolitical group or identity group of any kind. A recent article by John O’Sullivan in the Wall Street Journal takes up the issue of the new limits on free expression in the name of protecting religious and ethnopolitical group sensitivities. The article is an excellent treatment of these issues and I highly recommend it.

I have been a pretty standard liberal Democrat all my life, but recently I have been more critical of the left’s retreat from First Amendment protections. I’m talking about the left’s willingness to restrict symbolic expression that is critical of an ethnopolitical group or identity group of any kind. A recent article by John O’Sullivan in the Wall Street Journal takes up the issue of the new limits on free expression in the name of protecting religious and ethnopolitical group sensitivities. The article is an excellent treatment of these issues and I highly recommend it.

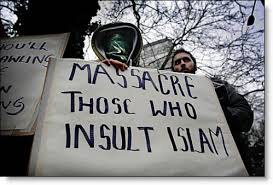

The harsh and anti-democratic strand of jihadist Islam has successfully scared enough people into restraining free expression in the form of restricting criticism of religion and political culture. Earlier in the history of free expression, O’Sullivan explains, the predominant restrictions on speech were with respect to obscenity, pornography, and language that was sexually explicit. The purveyors of these restrictions were moralistic and believed themselves to be defending proper standards of society. Political speech was strongly protected. But now, the calls for restrictions are designed to limit the political speech of others and consider off-limits the entire array of topics surrounding religion and politics. Obscene and pornographic speech was limited on the basis of protecting the broad moral foundation of the culture, limiting speech that is critical of religion is justified on the basis of particular groups with each making their own demands.

Burning an American flag is considered political speech and symbolic expression that is protected. I can legally burn the American flag in the center of the town square as a symbolic statement of opposition to some aspect of American foreign policy. But if I burn the Koran, which would still be legal in the United States as politically protected expression, it will cause a different reaction. There is a suggestion that the US endorse an international blasphemy law that would define the Koran as so special that burning it constitutes a particular offense, rather than simply protected symbolic expression.

The traditional approach to protected speech is to ignore the content of speech but simply disallow symbolic expression that will cause imminent danger (yelling “fire” in a crowded theater).Yet feeling free to limit speech because words are supposedly so powerful and dangerous is a slippery slope that will slowly erode freedom.

The Answer: Education

One does not come into the world with established political ideology and sensitivities to managing group differences. Democracy and freedom of speech is advanced citizenship in a democracy and must be taught. Free and open societies, where citizen participation is rich and required, necessitate learning the habits of pluralism and democratic processes. The legal environment surrounding freedom of expression has drifted toward an oversensitivity to categorize speech is injurious and in constant need of management. We should not be in the business of restricting all sorts of pure symbolic behavior. Living amongst one’s fellows in a pluralistic, multi-faith, diverse environment requires living in a world that is not of one’s own making and is constituted by differences. These differences must be managed through the deliberative communication process which is by definition “contestatory.”

The lines and distinctions implied here are difficult. For example, do we allow street gangs to deface public buildings with racist slogans and call it “freedom of expression”? I presume it would be possible to define such activities as sufficiently harmful and capable of producing imminent danger, but it will depend on many factors. Slow and long term as it is democratic cultures must continue civic education that includes democratic values.

Power to the People! A Call for Citizen Engagement in Israel Palestine

I’ve got an idea that is not really so bold as much as it is ignored. My idea responds to what I consider to be a weakness in the political considerations that characterize the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And that weakness is the failure of sufficient input from the general populace. I mean meaningful input taken seriously. Polls in both Israel and Palestine indicate that upwards of 60% of the population wants peace and find the two state solution to be sensible. It is true, according to a new poll of Palestinians, that the two state solution is falling away in popularity. But it can be reinvigorated and it does represent something the Palestinians support. A few people (e.g. Hamas, settlers, elites) cause a lot of problems and their messages are sometimes confused with consensus. Moreover, political elites cannot always be trusted and are subject to their own strategic manipulations. We’ve seen nothing but failure in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict even though it has been characterized by diplomatic influences.

In spite of all the political contact between the two sides the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is mired in complexity partially because the approach to peace building is not sufficiently multifaceted or inclusive of popular consciousness. Any sort of “people-to-people communication” can improve grassroots contact between the two sides, build coalitions, and engage ordinary citizens. But these forms of contact must also bubble up to influence political leaders.

I’m calling for groups of Palestinians and Israeli Jews to organize themselves into participatory groups characterized by democratic mechanisms that parallel the spread of recent nondemocratic dynamics. There are five other qualities that should be descriptive of these groups: first, these groups should be deeply integrated into the various communities; participants should be representative of the population, not elites. Two, these groups must be interdependent such that what happens in one group influences another group. Borders, population characteristics, and security matters are examples. Three, these groups have to be repeated often enough to discover consistent patterns that represent defensible conclusions. Four, they must be governed by principles of deliberation – some of which are discussed below – and democratic and public sphere criteria are expected. Finally, these groups must produce some sort of product and make it available to the public, which should be following the discussions anyway.

I do not intend for these groups to be revolutionary. They are grassroots movements designed to achieve a sustained message that typifies as much as possible population sentiments. The gap between public opinion and the perspective of the elected elites should be closed or constrained. The goal is to drive a reform agenda that improves the relationship between the populace and the government. These discussions should be as open and public as possible with the media performing their best function as a megaphone that reaches broad populations. The meetings should perform a legitimizing function and help find a path leading to some productive solutions.

Participatory Democracy

There are more models and procedures for citizen participation then we can respond to here (click here for a description six models of citizen participation), but a standard model of participatory democracy is best. This is a general term that refers to democratic procedures and representative decision-making. That is, nonelected citizens have decision-making power and the communication within these groups empowers individuals and promotes their cooperation. Participatory democracy is a model for social justice and the relationship between civil society and the macro political system.

It is true that participatory democratic discussions are historically idealistic and can be abstract but there are a number of success stories and advantages under certain circumstances. Organizing such groups is not easy and requires political will but it remains a relatively unexplored avenue. Finding a pathway to peace is a social construction that must include public debate and discussion. If these proposed participatory groups can establish themselves and maintain consistency they will be less vulnerable to the destructive influences of extremists on both sides. And managing these extremists – these few people who cause a lot of trouble – is particularly important in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict because these extremists will do anything to prevent productive solutions. Deep and widespread citizen engagement is probably necessary to build a foundation for a new political order that will be necessary if this conflict is going to be at least managed if not resolved.

There will be more on how to develop, organize, and structure these proposed public discussion in future posts.

Seeing Media Bias Everywhere Is Bad for Democracy – and Peace

There is a well-known study conducted in 1985 that ran a perfectly simple clean little experiment. One group favorable toward Israel and another group supportive of the Arabs were exposed to identical news stories about the violence in Lebanon in 1982. Even though both groups saw the same story, and all conditions of the experiment were the same, each believed the coverage was distorted and biased with respect to their own side; that is, they thought the media was hostile to their side. This is termed “the hostile media effect” and it very simply refers to the tendency to prefer your own group (either pro-Israel or pro-Arab) and distort perceptions of an “out” group and thus believe that the media are hostile to your side but lenient and supportive of the other side.

There is a well-known study conducted in 1985 that ran a perfectly simple clean little experiment. One group favorable toward Israel and another group supportive of the Arabs were exposed to identical news stories about the violence in Lebanon in 1982. Even though both groups saw the same story, and all conditions of the experiment were the same, each believed the coverage was distorted and biased with respect to their own side; that is, they thought the media was hostile to their side. This is termed “the hostile media effect” and it very simply refers to the tendency to prefer your own group (either pro-Israel or pro-Arab) and distort perceptions of an “out” group and thus believe that the media are hostile to your side but lenient and supportive of the other side.

Given the orgy of news coverage surrounding the war in Gaza, and the inevitable outcry about media bias, I thought I would clarify some distinctions and explain the social scientific foundation of media bias. More journalists and reporters work more diligently to present a balanced view of the conflict then the public gives them credit for. But the same journalists will tell you that their good efforts to be balanced are for naught and they are flooded with mail claiming bias regardless of what they do. This tells you that the bias probably comes from the consumer of the message rather than the producer.

The general tendency to see bias is common enough. One of the most well-established relationships is between message distortion and group identity. If you sort people into two groups (e.g. Israelis-Palestinians) this immediately sets into motion a series of processes that influence how messages are interpreted. And, these interpretations always favor one group or another including interpreting messages as biased against their own side. The results of the 1985 study referred to earlier have been replicated with numerous topics and events. We prefer to think of ourselves as treating people equally or respecting diversity of all sorts but the truth is we strongly identify with groups and define ourselves according to group membership.

From a rather straightforward evolutionary perspective, any exposure of your ingroup to negative information is perceived as a potential threat. This stimulates our sense of self protection, which takes precedence over other cognitive processes, and causes us to question the nature and quality of the information. Claiming that the media are biased against us or the information is substandard allows group members to minimize the inconsistency between their group favorability and information inconsistent with maintaining their ingroup status.

Moreover, the more one intensely identifies with their group – such as a religious group or ethnic identity – the more individuals feel potential threat and the more intense is the relationship between group identity and sensitivity to information threats. These relationships are further intensified when group members consider their group to be particularly threatened or vulnerable. If you ask a strong supporter of Israel or a Palestinian whether or not they feel their group is vulnerable, or threatened, or disrespected they will certainly answer in the affirmative and consequently are more responsive than most to information threats.

There are of course numerous consequences to the distortion of perceptions and information resulting from group identity – sometimes deadly consequences – but the threat to democracy is a problem that receives less attention than psychological ones. There are three of them: one, the quality of information failure. Information is discounted or judged negatively sometimes when it should not be. It becomes difficult to find common information acceptable to both sides which is necessary for conflict resolution. Secondly, group identity distortions result in political polarization. The two sides of an issue see themselves as more extreme than they might actually be and retreat to more extreme positions which makes it even more difficult to manage problems. And third, the sense of being threatened or the recipient of hostile media attention creates conditions that justify more extreme or even violent behavior. The group considers its existence to be in jeopardy and this justifies more extreme behavior in the interest of “protecting themselves.” It is analogous to increasing constraints on civil rights in the face of terrorist activity.

How do we moderate group identity affects? We will pay some attention to that issue next week.

The Paralysis of Choice

Ever since Kahneman and Tversky’s groundbreaking work we have accepted the fact that humans just aren’t very good at choices and keeping the best interest of everyone in mind. We believe our thinking and decision-making processes are clear and logical when in fact we are inconsistent in many ways. I presume most readers of this blog are familiar with this general pattern and I will not elaborate on it except to say that we make many types of mistakes: we exaggerate what we know; we overvalue some objects for illogical psychological reasons; quality information sometimes does not matter; we shift choices for ideological reasons; we unconsciously seek out confirming information; on the average, humans are more unreflective, impulsive, and subject to illogical influences than we are “rational.” A recent article in The Nation captures these issues.

But those of us interested in deliberation, political communication, group decision-making, and group processes cannot easily abandon the issue of choice or making decisions. We cannot simply throw up our hands and say “people are irrational.” We must continue to explore these matters and find ways to improve.

For starters, we should confront our historical ideology about the value of choice. As a liberal democracy and market economy we naturally believe that choice is better, and the more choices you have the freer the market and the richer the environment. But some who have written about this issue demonstrate how we are constantly anxious and unsure of ourselves because of so many choices. We are constantly in the state of insecurity and questioning whether or not we have done the right thing whether it is a choice of a school, a food item in the market, a financial plan, or any number of other choices.

Still, one of the most interesting and creative ways to think about choice is the role it plays in a democratic society. In other words, choice can be related to political ideology such as those choices explained in Gladwell’s The Art of Choosing or Ben-Porath in Tough Choices. One political argument for the role of government is that it levels the playing field; when the distribution of money and resources becomes unequal government steps in and constrains choice markets. Clearly we do not make choices in a perfectly rational market – some members of that market have fewer choices than others and of less quality – so a middle force such as a government steps in and levels the playing field choices.

Again, part of this intervention is “behavioral economics” where the state or a business manipulates the environment so you will make certain choices. For example, automatically transfer a portion of payroll to a savings account and require the individual to “opt out” rather than “opt in” which increases the statistical likelihood of saving.

No, those of us interested in the communication process, the deliberation process is epistemic; that is, communication can produce new knowledge and new possibilities. Difficult problem solving is not simply a matter of choosing a correct choice that is more rational than another, or selecting an option that has maximized value. Much of this work in “choice” and the processes that influence choices is less relevant to deliberative theorists. Deliberative communication emerges from the literature on deliberative democracy and is rooted in the advantages that accrue from reciprocity. “The basic premise of reciprocity is that participants owe one another justifications for their institutions, laws, and public policies that collectively bind them.” This means that justice and the legitimate acceptance of social and political constraints on a group must emerge from a process where all parties have had ample opportunity to engage in mutual reason-giving. From reciprocity flows respect for the other. Scholars also refer to publicity and accountability as essential conditions of deliberative democracy. That is, discussion and decision making must be public to ensure justifiability, and that those who make decisions on behalf of others must be accountable. Binding decisions lose moral legitimacy to the extent that they have been made in a manner unavailable to the public, or by individuals who are not accountable to their constituencies.

What is particularly important about deliberation from a communication perspective is its ability to transform the perspective of the individual. Election-centered and direct democratic processes value the individual, but focus primarily on the opportunity to participate. Deliberative processes draw on communication in the form of discussion and argument with the aim to change the motivations and opinions of individuals. The deliberative process contributes to a changing sense of self and identity because participants are immersed in a social system that manufactures new ways to think about problems and orient toward others. This deliberative social system moves people out of their parochial interests and contributes to a broader sense of community mindedness, as well as providing new information that clarifies and informs opinions. The issues pertinent to categorical choices are relatively inconsequential to deliberation.

Striving for “Collective Reasoning”

Consider the example below from Sunstein of “incompletely theorized agreement.” Incompletely theorized agreement is when two groups in disagreement agree on the preferred outcome but disagree on a more general theoretical rationale. A deeply religious Christian and a scientist might both want to protect a living species from extinction and work together to accomplish that but for different reasons. The Christian may be motivated by the belief that the species is part of God’s grace, and the scientist justifies his preferences on the basis of a balanced ecological system. The solution is incompletely theorized because they agree on the most practical problem solving level but disagree at a deeper theoretical rationale. Israelis and Palestinians disagree on a deeper fundamental level. An Israeli Jew might believe the land was bequeathed to them in the Bible and they are doing little more than returning to a historic homeland. A Palestinian would hold that the Jews were colonialist in their domination of the land, and that the Arabs are the indigenous population. The goal is not to battle it out trying to change the mind of the other on such fundamental issues, but to move to a different more practical level of cooperation that is shared by the participants rather than focusing on the theoretical rationales that divide them so. This is collective reasoning.

You have heard the quip “come let us reason together.” Well, it is possible to reason together and during quality deliberation it is termed “collective reasoning.” It is primarily concerned with what is termed “rational cooperation” with particular emphasis on conflicts between divided groups. Collective rationality involves more than decisions about desirable outcomes that benefit only an individual’s judgment about value. For example, if everyone in a community contributes a small amount of money to improve the road in their community and incurs an individual cost, but a collective benefit (improved roads in the community), then this is a decision based on collective rationality. It is sensible for the whole group to accept such a decision. Of course the individual cost can be too high for some or repugnant to others, and there can be debate about the actual cost and required contribution, but this entire process still represents a form of collective rationality. A decision to contribute in this example is not governed by pure individual rationality otherwise an individual might decide to free ride or not contribute at all.

Part of the power of deliberation is its reliance on collective reasoning which is mutually beneficial cooperation. This prompts the question if collective reasoning is based on mutually beneficial cooperation then the deliberative theorists must ask how do we produce this cooperation, and how do people benefit from it? The communication patterns and social conditions that move people from their individual rationality to collective rationality are also of considerable interest. Most people begin a conflict with a clash of individual perspectives, narratives, and data. The first impulse is to conclude that one’s own choices are best for him or her and then go about the individually rationalistic process of trying to maximize your own rewards and not deviating from these efforts. It is only when groups continuously fail, or when they are experiencing a hurting stalemate, that they begin to shift their thinking toward cooperation rather than conflict. At some point when the efforts at resolution get serious, or when the likelihood of failure and loss increase, participants in conflict begin to reason seriously and collectively. But if deliberation is assumed at one point to be worthy, and not only for its democratic proclivities, but for its epistemic possibilities then cooperation in tasks such as gathering information, challenging interpretations, and making inferences is germane.

Collective reasoning is a communicative exchange designed to manage a problem. It is distinct from conversation in that collective reasoning seeks to answer questions and solve problems and is a more structured form of social contact. It includes justified judgment which is a conclusion or decision supported by relevant information and reasoning. To be a little more specific, collective reasoning expects the participants to acquire a justified judgment that would be superior to their individual reasoning. This superiority includes the benefits of cooperation; in other words, the collectively justified judgment may not meet all the desires of an individual but it satisfies them sufficiently as well as others. By way of illustration, if everyone in a group had the same information and made the same judgments about it then there would be simple agreement and deliberation to solve problems would be unnecessary. But if the group is characterized by unjustified judgments, and the accompanying tensions and disagreements, then they must expose themselves to some exogenous input – new information contact with someone outside their group experiences that can contribute to additional collective reasoning. This is conceptually similar to Simons’ problem of bounded rationality which is that individuals cannot go beyond the boundaries of their own abilities and knowledge. Deliberation and collective reasoning improves the availability of information and allows for the cooperative advantages that come from deliberative discussion. Even if someone else has inappropriate, inaccurate, or manipulative information such conditions can still sharpen my own considerations and potentially lead to new ways of solving problems.

How Many More Decades Do We Have To Watch This Silly Shuttle Diplomacy between Israel and Palestinians? It doesn’t work!

How much longer do we have to watch an American diplomat shuttle back and forth between Israel and some neighboring country? From Henry Kissinger in the 1970s to John Kerry it’s all the same process. The tennis match image comes to mind and I would use it if it were not such a cliché. I’m increasingly coming to the conclusion that it’s all pointless and that comes from somebody who believes in talk. Even though I recognize that talk is slow and there’s nothing magical about it, there comes a point when you have to ask yourself whether it’s all worth it.

When talk fails it is usually for one or a combination of three reasons. One, it’s the wrong kind of talk. Two, the wrong people are talking, or three the structural conditions are interfering. All three are at work in the Israel-Palestine shuttle diplomacy. It’s the wrong kind of talk because the two sides are unprepared to have serious political conversations when they need more authentic mutuality. The wrong people are talking because there should be more conversational work at the civil society and interpersonal levels. The structural conditions could be improved to increase democratic forms of communication, inclusion, and more creative and grassroots routes to problem-solving.

Palestinian supporters often boldly claim that resolving the Israel-Palestine conflict is the key to bringing greater peace to the region and although this is an exaggeration supporters have been successful at turning the conflict into the symbolic prototype for all the world’s problems. I think about the ugliness in Syria, the savagery of militant groups, rising religious authoritarianism, escalating economic inequality, Iran and the spread of nuclear weapons, and then discover that serious people in Washington want to talk about West Bank Palestinians!

Of course the conflict must be resolved or at least managed into agreement. But the biggest beneficiary of any resolution is going to be Israel. How long can Israel continue to occupy the West Bank? How long can it remain a security state? How long can Israel maintain its successful democracy and market economy if it has to oversee 2 million Palestinians?

There will not be peace between Israelis and Palestinians – real peace when barriers can be removed – until it emerges from democratic impulses born in civil society. When Palestinians demand more of their own rights from their own leadership they will be in the position to demand rights from Israel. America should be supporting Palestinian political infrastructure by working on the economy, improving governance and civil liberties, and expanding business practices that can rationalize relationships and serve as a foundation for future democratic relationships. But the conflict remains intractable and diplomats like Kerry are operating at the wrong levels.

Muslims and the Jews tell two different stories both of which are fueled by media and policy decisions. Israel tells a story of historical oppression and discrimination culminating in the Holocaust and the creation of the state of Israel. Jews feel vulnerable and threatened. Muslims feel disrespected by the West and the victims of media biases that portray them as fundamentalist and inherently backward, not to mention violent and religiously extreme.

These narratives produce tensions between Islam and the West and are decisive. They make for a cultural divide which results in polarization of identity issues, adversarial framing of historical matters, and rejection of any sense of shared responsibility for conflict. US policy and world media circulate these images and messages to the detriment of any sense of complementarity between the two.

In my opinion, there are two things that can happen: the differences between these stories can be emphasized, which will lead to increased intensification leaving the disputants to be trapped inside their own threatened identity. And the macro level of official contact will continue to founder. Or, these narratives can be reframed in order to seek points of convergence where it is possible to formulate cooperation and mutual affinities that direct them away from a “conflict-saturated” reality. Rather than rival narratives, Jews and Muslims can avoid the drift toward polarization and begin to tell a new story, one that affirms a distinctive identity while acknowledging the “other.” I choose this direction.

New Trends and Knowledge-Based Journalism

The United States has a long tradition of “objective” journalism. At least we tell ourselves that objectivity is an ideal to strive for. In some other news cultures there is not even the pretense of objectivity. A newspaper, for example, will have a perspective and they will state it clearly and the reader is expected to know the perspective. So there is a communist newspaper, a socialist newspaper, a business capitalist newspaper, and so on. The reader understands the perspective and reads the news with the interpretive lens called for.

But whether there is objectivity or perspective the news is still a sort of “lecture.” The journalist is an authority and the reader is “learning” something. Given the distrust of journalistic institutions, sinking circulation, weak citizen engagement, and low credibility for news this monologic approach is clearly dying off.

But modern incarnations of journalism are more influenced by user generated possibilities as well as new technology. Fueled by the ideas of public journalism and a reinvigorated public sphere where ordinary citizens could communicate about ideas, contemporary thinking about journalism includes more interactive possibilities. (A good reading on these and related matters is by Marchionni in the journal Communication Theory volume 23, 2013) The reader can use various web tools to participate in journalism and this can include supplying content and forming a sort of collaborative journalist-citizen relationship.

These new trends are interesting and grounds for improved engagement between the public and journalism institutions. But I am less concerned with what journalism practices are called (public, participatory, interactive, or conversational) then I am with journalism’s quality and reliability. I prefer the term “knowledge-based journalism” as described by Patterson in his book Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism. A thorough essay on knowledge-based reporting appears here.

Knowledge-based reporting tries to maintain the tradition of accuracy and truth but recognizes that most of the time the news report will simply do its best to get the best version possible. Still, knowledge-based journalism relies on its tradition of verification. Journalism is not fiction, or entertainment, or propaganda. Patterson, as described in the essay available in the link above, argues that journalism should adopt the thinking and processes of “science.” That is, the journalist formulates guesses and hypotheses, gathers facts, and knows how to apply other facts.

Walter Pincus wrote an article for Columbia Journalism Review accusing journalists of being narcissistic primarily because of journalism’s interest in larger long-term investigatory projects that are likely to bring Pulitzer prizes. The article makes a few counterarguments warning against the narcissism that prompts journalists to devote too much time to one story rather than making a variety of issues available to readers.

But deep knowledge and competence and specialization are at the core of knowledge-based reporting. Patterson reminds us that journalists who are uninformed and lack detailed knowledge are more subject to manipulation by sources, make more mistakes, and vulnerable to a few experts.

Finally, communication scholars have pointed out that journalists are just fine at providing the who, what, where, and when but fail miserably at the “why” question. I have asked journalists about this and they typically reply that they do not want to turn the press into a school text. But this hardly seems like an inevitability. And with new technology and graphics the possibilities for likely presentations and explanations seem ample. I will not repeat the cliché about democratic and free societies relying on quality information. But “democratic and free societies rely on quality information.”

Syria As the Prototype for the Loss of Democratic Freedoms

In a recent Wall Street Journal article Puddington and Kramer reported that there has been a decline around the world in political rights and civil liberties as measured by Freedom House. True enough, the measurement of these things is not an exact science but Freedom House does a decent job of identifying key variables and definitions correlated with cultures that privilege democracy and civil liberties. After some years of improvement because of democratization around the world the general trends have been in decline. The authors report that 54 countries had registered declines in political rights and only 40 registered gains.

The reasons for these declines are interesting and the current conflict in Syria poses a particularly fitting example. The case of Syria is a typical model of authoritarianism that holds its power for a period of time through force and intimidation and then loses that power to violence and revolution (think Egypt, Tunisia, Libya). But even more interestingly the earliest mistakes are confusing violence with politics; that is, organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood or any other anti-government faction resorts to violence because there are no legitimate outlets of political expression and change. There’s a rather simple video you can watch which lays out the structure of the conflict in Syria and is actually a model for many other places. The video is brief and simple but is a template for any number of political situations. It is called “Syria explained in five minutes.” The decline in political freedoms is correlated with the political processes on display in the video.

Many of the losses of political freedom are associated with efforts to sabotage the Arab Spring. Religion and illiberal factions are reinforced for damaging democratic gains. And there is the very damaging influence of outside powers that imagine democratic gains as contrary to their own interests. Hence, countries like Russia, Iran, and Venezuela have conspired to keep Assad in power. Moreover, the Middle East is no longer the worst scoring region of the world when it comes to measurements of freedom. Russia has increased the intensity with which it silences groups, denies rights to nontraditional groups such as gays and lesbians, and uses its oil clout to interfere with any political process that is contrary to its interests. Russia cracks down on NGOs, civil rights activists, journalists, and any political opponent who poses a real challenge.

Russia, China, and Venezuela light the way for authoritarian governments that dominate media, security, as well as legislative and judicial branches of government. They do this mostly by blindly supporting centralized authoritarian governments such as the military government in Egypt or of course Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Syrian opposition to Assad is highly fractionated and is composed of the Free Syrian Army (deserters from Assad’s army), numerous Islamic groups from more extreme (e.g., “Battalion of Truth”,), to less extreme (Liwa al-Tawhid “Battalion of Monotheism”). There are Kurdish groups and independent groups not to mention attempts to form organizations that are more inclusive such as the “National Coalition.”

Clearly, the aggressiveness of extremist Islamic groups keep democratic pressures at bay and their presence in places like Syria will prevent democratization for a generation to come. And, finally, perhaps even more disturbing is the paralysis of places like the United States. We have said little and played an insignificant role in Syria because there’s no group to identify with and support. Secretary of State Kerry has worked to broker discussion at the macro level but the US is less engaged then countries like Russia and Iran. This can’t be good.

Language And Its Power

Language certainly has the power to direct you towards pre-selected portions of reality. It makes it possible for false comparisons and confusion over categories of meaning. For example, there is a common statement that circulates in the public that is not only a facile generality but dangerous. If you actually believe this statement, if you are ensnared by its rhetorical trickery and literally accept the two propositions as being equal, then it reveals you as a less than rigorous thinker who cannot recognize or make important distinctions. If you accept the equivalence of the two propositions you are likely to put yourself and others in danger by being paralyzed with an inability to act and justify definitional clarity that allows for clear decision-making. The dangerous cliché I’m talking about is:

One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.

If you believe this then Osama bin Laden and Al Qaeda are the same as what might be considered a defensible national liberation movement. The semantic foundation of the cliché implies that nothing matters except perspective. It’s a cliché championed by terrorists because they want to present their own causes as positive and justified. And the logical extension of this thinking is that no violent act can be too odious because it is all in the service of national liberation. Terrorists love this phrase because it blurs the distinction between goals and the means to achieve the goals, when in fact no political movement can serve as a justification for terrorism.

This cliché cannot stand and we need more political leaders and public intellectuals to condemn it. There needs to be public discussion and argument. Freedom fighters who are truly struggling against oppression do not kill innocent people and sow panic and confusion – murderers do. Why would the democracies and liberal political regimes around the world allow the word “freedom” to be used in this way? Terrorists do not bring freedom they carry fear and oppression. The best reading on this is by Boaz Ganor and can be found here. It is crucial to make the distinction between terrorism and national liberation.

Let’s try to be a little clearer about terrorism. As Ganor describes, terror is (1) violent. Peaceful protests and demonstrations are not terrorism. Terrorism is (2) political. Violence without politics is simply criminal behavior. And (3) terrorism is against civilians with the goal of creating fear and confusion. It mixes with the media to produce anxiety. So what is not terrorism? Terrorism is not accidental collateral damage when the original target is military. Using citizens as shields places the onus of responsibility on those manipulating the citizenry, not those who initiated the attack if it was against a military target. It is also important to recognize those situations where targets of violence are clearly military and uniformed soldiers. Using guerrilla tactics does not necessarily mean terrorism.

It is important, too, that motives be taken into consideration. The real thorny problem is the idea that any form of national liberation – believed sincerely by a presumably oppressed group – justifies violence that is not considered terrorism. This perpetuates the dangerous relativism of the cliché. The hard mental work of distinguishing terrorism from other forms of violence is important if we are going to pass legislation to protect the public, have effective international cooperation, and assist those states struggling with terrorism.

If enough people genuinely accept this relativist cliché then all bets are off. Any sort of violence can be justified and the international community will have a collective shrug of its shoulders essentially saying, “who cares” because someone considers the violent group “freedom fighters” wrapped in vacuous rhetoric designed to justify violence. As difficult as it is to fashion a precise definition of terrorism, it is equally as difficult to imagine accepting Al Qaeda and jihadist attacks against the United States as the work of “freedom fighters.”