Blog Archives

Is this the Muslim Martin Luther?

The below was first posted in March of 2014. Thought it would have new interest given events in Turkey.

The photograph above is of Fethullah Gulen who Victor Gaetan writing in Foreign Affairs compared to the Muslim Martin Luther. Interestingly, I have been writing a little bit about Gulen recently in a book that I’m finishing up and during my research I had become a little intrigued with Gulen. You can find the article in Foreign Affairs here.

A typical descriptive statement about Islam over the last decade is that it never experienced a Reformation. It is true enough that Sufi-ism and scholars such as Said Nursi inspired new more humane schools of thought but they remain marginalized. Much of Islam, not all, is harsh and rooted in the political and military conditions of the ancient world and there has never been a moderation of these tenets by a Muslim Martin Luther. There has never been a Muslim Reformation. Martin Luther was an influential and controversial figure in the Christian Reformation movement. He was responsible for entire new lines of thinking in Christianity and set in motion a sort of enlightenment. Luther had a desire for people to feel closer to God and this led him to translate the Bible into the language of the people, radically changing the relationship between church leaders and their followers. Martin Luther is generally associated with rooting out corruption, preventing religion from being used as a tool for political power, and humanizing the church his anti-Semitism notwithstanding.

Even at the risk of exaggeration, many feel the contemporary version of the Muslim Martin Luther is Fethullah Gulen. Gulen is a Turk who has been in the United States since 1999. He has worked to promote a modern school of Islam and is an Islamic intellectual committed to secular education, economic development, democracy, and acceptance of scientific knowledge.

Gulen has taught that Islam should devote more energy to public service and be separated from politics as much as possible. His emphasis on helping others and doing good deeds in the community is consistent with much Koranic teaching and directs attention away from political organization. This is in sharp contrast to the Muslim Brotherhood whose ascendancy in the last half-century has argued that the state should be Islamic and armed struggle is a moral and spiritual obligation. Moreover, Gulen is committed to education, including science and math, and has over 1000 schools around the world with video and instructional material made easily available to students.

As you might imagine, Gulen is not popular with modern-day Islamists. He has been exiled in the United States for many years and clashed with Erdogan over foreign-policy and authoritarian politics. Gulen is a strong supporter of democratic dialogue and he has chastised Turkey and other Islamic countries for poor treatment of journalists and a failure to engage sufficient constituencies over issues such as the Gezi Park protests.

The Gulen movement upholds numerous liberal conditions such as the belief in the intellect and the fact that individuals are characterized by free will and responsibility to others. Not all of Islam divides the world up into categories such as dar al-harb (the house of war) and dar al-Islam (the house of peace) but understands humans as more coherent and integrated. A verse in the Koran states that “there is no compulsion in religion” which emphasizes the individual intellect and freedom of choice.

Gulen is both careful and brave. He will not be intimidated and continues to speak up even in the face of the easy violence that could confront him. While Erdogan continues to clamp down on Turkey with Internet censorship and control of the judiciary, Gulen continues to infuse Islam with the teachings of tolerance and democratic sensibility.

Religion and Foreign Policy

In the modern era religion has played a relatively small or insignificant role in foreign policy, especially among academics and professionals. International relations are assumed to be subject to rational processes and the primary motivating force is not religion but maximization of gain and minimization of loss.

But the Iranians following the revolution of 1979 have been the first significant departure from this trend. Iranians have defined themselves as fundamentally Islamist and any effort to organize against them, any war or confrontation, is considered an attack on Islam. Global jihad and pressures on other Islamic countries not to partner with non-Muslim governments are part of the growing entanglements between foreign-policy and religion.

The United States is oblivious, and I don’t mean that as a compliment, to issues in religion in foreign policy. They miss theological underpinnings all the time and have naïvely misread and failed to grasp incidents such as the Iranian revolution, Islamists objections to our presence in Saudi Arabia, all while we blithely armed Islamists in Afghanistan because we thought we were thwarting communism. Even our efforts at democracy promotion have failed in the face of confrontations with religious tenets that we fail to understand, ignore, and consider to be little more than inconsequential background.

And probably the biggest blind spot for the United States has been the published documents by ISIS and Al Qaeda members detailing terrorism with a vision of Islam. These documents make reference to the creation of a global caliphate; foment a religiously apocalyptic narrative; and use religious motivations to recruit young believers. The US continues to fight the war on terrorism as a military and security matter and not a religious one. Theology animates ISIS such that killing them only creates more committed actors who will find new ways to subvert their enemy, namely, the US.

Interestingly, it is a form of political correctness that keeps the US from acknowledging the theological underpinnings of terrorism or any other foreign policy with a basis in religion. What I mean is that American leaders do not want to be perceived as attacking Islam or being critical of Islam even if it is religious tenets rooted in Islam that justifies violence in its name. Secretary of State John Kerry and Obama might refer to gun laws, history, morals, economic deprivation, or some aberration but they never tie violence or some aggressive behavior by another group directly to theological principles of Islam. I can understand the delicate diplomatic position of the President of the United States such that he does not want to prance around the world condemning world religions. In fact, organizations like ISIS want to divide the world into Muslims and non-Muslims and blaming entire religions would play right into their hands. They succeed at this to the extent that the US blames Islam or gets involved in military actions on land that is considered caliphate. Still, our policies will be ineffectual to the extent that they fail to consider religion in foreign policy.

It is not easy for the United States to all of a sudden adopt religious oriented policies or even to begin to use the language of religion in an effort to appease or seek a superficial identification with another political entity. That is why we must find other ways to weaken their theological basis. This includes empowering natural enemies, and providing improved social and economic progress in contested areas. We’re also losing the propaganda or information war as these religious oriented policies spread their beliefs. Organizations like ISIS and countries like Iran clearly embrace religion as part of foreign-policy. In the end, if we are to make progress in the information war we are probably left with Justice Brandeis’s adage about how “the remedy for bad speech is more speech.”

The Sunni-Shia Divide and Modern Consequences

Mohammed revealed his new faith in 610 and it was known as Islam or submission to God. He gathered followers quickly and by the time of his death in 632 had set the stage for the building of an empire. But the Sunni-Shia divide was the result of disagreement over future leadership. The disagreement was simple. The Shia believe that only the descendents of Mohammed could rule, and the Sunni believe that being part of Mohammed’s bloodline was not necessary. The Sunni were more powerful and have a long history of persecuting Shia.

There were further splits within the Shia (e.g. “the Twelvers”), the details of which are not of concern here, but the result is the modern-day distribution of majority Shia in Iran, Iraq, Azerbaijan, and Bahrain and about 40 countries are Sunni.

This modern ethnoreligious conflict

The current sectarian and political differences between the two are due in no small part to the Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran who instituted an Islamic government based on Shia religious principles. Organizations like Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood are Sunni and do not accept such a version of Islam. Saudi Arabia, a Sunni country, recently sent troops into Yemen (a key strategic concern to the United States) to repel Iranian supported agitators as well as the Houthis. Yemen shares a border with Saudi Arabia. And some scholars have argued that the Sunni puritanical sect known as Wahhbism was in response to Shia Iran. The tensions in Yemen, the Iran-Iraq war in 1980-1988, and the organization of militants in Afghanistan to fight the Soviet Union are all the result of Sunni-Shia tensions. And you might recall that Saddam Hussein was a Sunni ruling over a majority of Shia. Iran supports Bashar al-Assad even though he is an Alawite and a member of the Shia minority sect.

Sunni and Shia governments constantly worry about their grip on power, especially in the wake of protest movements in places like Tunisia and Egypt. The Arab awakening has spread along the sectarian divide especially when minority sects are the ruling power. This is true in Bahrain where Shia are the majority but there is a Sunni ruling family, and of course the Alawite in Syria rule over a Sunni majority. The Civil War in Syria is a classic sectarian tension and a proxy war between Sunni and Shia powers.

These authoritarian regimes, especially where a minority religious group rules over a majority, rely on authoritarian governments closely aligned with their military to maintain the order. These authoritarian governments are sometimes preferred because they result in stability. Sometimes leading scholars even suggest that these cultures are not going to be receptive to American reforms especially with respect to democracy creation. Consequently, they argue for the desirability of authoritarian regimes as illiberal as they are. But the Arab Awakening must be explained. Surely cultural, technological, and economic factors can be a combustible mixture. The Sunni and the Shia provide the spark for this mixture and bubble underneath most political change in the Arab world.

Cultural Differences and Conflict

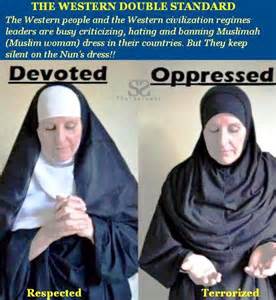

I know, I know. Dichotomies like the ones below are typically exaggerations and overly simplistic. But such distinctions also represent the real world of how people think. And even if differences such as the ones below are not perfect, they are the sorts of differences that must find their way into solutions. These distinctions also necessarily simplify issues and make them more manageable. Besides, they are better than the cartoonish “Clash of Civilizations.”It is simply true that two cultures such as Islam and the West do not share universal standards of argument and reasoning. It is not that they are incommensurate, but they are sufficiently different such that certain points of articulation must be discovered and addressed. Moreover, the religious versus the pragmatic traditions of the East and West respectively make for numerous points of disagreement.

A Islam-West conflict will be considerably different than other international relations conflicts, which might be more subject to rational negotiation and decision-making. But any conflict between an Islamic and Western tradition will be filtered through identity and made more difficult and sensitive by identity. A conflict will always have to recognize the centrality of identity issues and find ways to manage them.

Differences between Islam and the West with Respect to Conflict Resolution

Islam The West

| 1. Believe an image of violent Islam is predominant in the West.

2. Peace is defined by the presence of Islamic values.

3. Issues of “face” and “honor” are particularly important.

4. Discourse of peace is the exception.

5. Modern social science is not very relevant.

|

1. Islam and the West are incompatible and Islam is a threat

2. Peace is the absence of war and found in pragmatism.

3. These issues are important but somewhat less so.

4. Discourse of peace is normal.

5. Importance of the social sciences and managing conflict.

|

In my book “Fierce Entanglements” I cite 20 of these dichotomies but have only a few here for the sake of brevity and space. I think issues such as these deserve attention and I find that they get relatively little. One of our conundrums is that we currently live in an age of tremendous cultural difference recognition. Subgroups in a society demand recognition of their distinctiveness and the right to practice their culture even though it is at odds with the dominant culture. As a society, we increasingly take great pleasure in pointing to cultural differences.

But we’re much more hesitant when it comes to actually recognizing those differences legally and morally. When we generalize or categorize another culture we are quickly reprimanded and reminded of exceptions and variations. So, I do not know if all the distinctions referred to in the table above are justified, but they do represent a common template and for starters are worthy of discussion.

What do you think?

ISIS is for Real

After drawing attention in last week’s post to the Scott Atran article on how ISIS is a genuine revolution and should be taken seriously, I had a friend observe that I sounded more like a conservative than in the past. It sounded more like I was taking ISIS seriously and perceived them as a genuine threat. I had posted once before (see entry for October 31, 2015) that ISIS was failing and underperforming. This was interpreted by some as not taking ISIS seriously and assuming that they were some sort of upstart movement that would die out easily and quickly.

After drawing attention in last week’s post to the Scott Atran article on how ISIS is a genuine revolution and should be taken seriously, I had a friend observe that I sounded more like a conservative than in the past. It sounded more like I was taking ISIS seriously and perceived them as a genuine threat. I had posted once before (see entry for October 31, 2015) that ISIS was failing and underperforming. This was interpreted by some as not taking ISIS seriously and assuming that they were some sort of upstart movement that would die out easily and quickly.

Nothing could be further from the truth. I agree with Scott Atran that ISIS is a “real” revolution, that it is growing and increasingly attractive to many, that something should be done about it, and whatever we are doing now is probably not sufficient. Unlike many of the Obama haters I do not consider his patience, diplomacy, and slower hand to be signs of weakness. But there was recently a story in the New York Times making essentially the same point. What we are doing now to fight ISIS is not sufficient, but we should be approaching the problem from the long-game perspective and ultimate victory will take time.

ISIS’s violence is transcendental in that it is appeals to a sense of the sublime and gives serious meaning to its adherents with respect to their own destiny, power, and sense of the ultimate. ISIS does not need to see itself as composed of overwhelming numbers. No, it sees itself as a revolutionary vanguard leading the masses and informing them about what is to come. ISIS seeks a tremendous transformation. And the sublime appeal should not be taken lightly. ISIS is increasingly credited with technological and political sophistication and seems to be appealing to the 18-24-year-old group who report that they have some favorable attitudes towards ISIS. This is especially true among the downtrodden whose anger fits nicely into ISIS’s co-option of this anger. And, as Atran points out, these young people attracted ISIS are more willing to fight and engage in violence to defend principles they are not even sure of than are other young people willing to fight and defend democratic values against an onslaught.

ISIS is emerging as consistent with historical revolutions (e.g. French Revolution) where an abstract but powerful commitment to a spiritual force justifies about anything. Visions of universal equality or economic fairness have held equally as powerful sway as have dreams of the future governed by sharia law.

Finally, the rhetorical skills of ISIS and AQ must not be underestimated. They have, for example, reconstructed the concept of a caliphate – a political concept challenged by many historians – as an alternative to a meaningless material world. The caliphate justifies an expanded notion of jihad and holy war against infidels. ISIS leaders have changed maps and bulldozed territorial boundary signs as the remnant of Western colonialism and Sykes Picot rather than holy land that will be part of the caliphate.

Talking to ISIS will probably be futile for some time to come. The two sides are classically incommensurate in that the West engages in moral disagreement from a pragmatic perspective that is without foundational principles. And ISIS is steeped in Islamic foundational principles that are generative of its discourse. Perhaps one day there will be sufficient bridging discourse that the two sides have at least initial commonalities that can strengthen the bridge rather than only the supporters on each side.

The Concept of Peace in Islam

In the West peace means predominantly the absence of war. Peace is the result of institutional agreements or the regulation of behavior and mutual negotiations about what is considered threatening or unacceptable to each side. Solving conflicts is a rational problem-solving activity and reason is primary. It is possible to settle Islamic conflicts and make peace, but it must be done within the conceptual context of the Koran. And in many ways this is not so different from other religions.

In the Muslim tradition peace is associated with human development and justice, but justice that is rooted in the Koran more than secular reason. Peace implies the maintenance of human dignity and a sense of balance and coherence in society. Peace in Islam is associated with God and considered to be one of the names for God. There are roughly 5 approaches to peace.

Power: In Islam sometimes it is necessary to simply assert political power and use secular tools to manage disorder; disorder and chaos are considered threats to Islam and must be dealt with. This approach emphasizes political necessities because the population or some aspect of the community is threatening the good order of Islam.

Peace Based on Koranic Law: Peace is a condition of the Koran and violations of rules are inconsistent with peace. The values of the Koran must be in place or the community is characterized as unstable and disorderly. A situation in which these values are not present may be characterized as disorderly, unstable and un-Islamic. Sometimes this approach can be abused because of the easy or casual assertion that Islamic law is being violated and thus harsh consequences are justified.

Peace Through the Power of Communication: There is a tradition of mediation and arbitration (these are fundamentally communicative in nature) in Islam. The concept of balance remains important here. This is the notion of peace which is consistent with the West and some secular approaches. It recognizes that balance in society is not only maintained by religious precept but by restorative justice. Consequently, those who have experienced loss can be compensated or when one family is disadvantaged by another balance is restored through repayment or restoration of some type.

Peace Through Power: Islam also calls for nonviolence and the maintenance of security even when these things must be maintained through traditional power. Again, the approach is rooted in a concept of coherence and balance where peace is maintained by responding to the other’s needs. Secure and authentic peace must be rooted in human dignity.

Peace Through the Regard for the Other: The love of God in the precepts of Islam make for a broad and encompassing harmony. Again, this is a place where the religious and the secular can meet because one is expressed by the other. Each person is able to turn inward and find the value in the other through Islam. There is room here for change and transformation including the possibility of redemption.

Islam recognizes that humans are social and must live together. Thus, there has developed a line of thinking from religious documents to the daily organization of society. This is essentially the relationship between Islam and the state. There is much in Islam that puts the community’s interest first. But most important of all is the consistency between religious principles and the political system which always provides an avenue of redress. The community always has its mundane and routine needs but these are rooted in tradition, respect, and consistency with Islamic law. Islam is a classically collectivist culture where individuals are less important than the collectivity. Individuals are punished or judged to the extent that they disturb the good order of the community. The individual counts little by himself – a concept quite different in the West. It is the clan or society that has the right to protect itself by punishing a recalcitrant individual. Someone’s guilt or innocence is couched in the context of threatening or sustaining the community. And there must be an authority (textual or human) responsible for maintaining community order. This is regarded as absolutely necessary since society without authority is impossible.

9 Headlines You Will See in the Future

The below is from Tom Englehart and I thought it was particularly good and deserving of distribution so I reproduce it here on my blog. Tom runs TomDispatch.com and there’s information at the end of the text if you would like exposure to more of Tom’s thinking. Tom’s point in the second paragraph is well taken – whoever thought we would be on our way to a caliphate that out maneuvers us in social media. I think the issues for what America has to learn are pertinent.

Writing History Before It Happens

Nine Surefire Future Headlines From a Bizarro American World

By Tom Engelhardt

It’s commonplace to speak of “the fog of war,” of what can’t be known in the midst of battle, of the inability of both generals and foot soldiers to foresee developments once fighting is underway. And yet that fog is nothing compared to the murky nature of the future itself, which, you might say, is the fog of human life. As Tomorrowlands at world fairs remind us, despite a human penchant for peering ahead and predicting what our lives will be like, we’re regularly surprised when the future arrives.

Remind me who, even among opponents and critics of the Bush administration’s invasion of Iraq, ever imagined that the decision to take out Saddam Hussein’s regime and occupy the country would lead to a terror caliphate in significant parts of Iraq and Syria that would conquer social media and spread like wildfire. And yet, don’t think that the future is completely unpredictable either.

In fact, there’s a certain repetition factor in our increasingly bizarro American world that lends predictability to that future. In case you hadn’t noticed, a range of U.S. military, intelligence, and national security measures that never have the effects imagined in Washington are nonetheless treasured there. As a result, they are applied again and again, usually with remarkably similar results.

The upside of this is that it offers all of us the chance to be seers (or Cassandras). So, with an emphasis on the U.S. national security state and its follies, here are my top nine American repeat headlines, each a surefire news story guaranteed to appear sometime, possibly many times, between June 2015 and the unknown future.

1. U.S. air power obliterates wedding party: Put this one in the future month and year of your choice, add in a country somewhere in the Greater Middle East or Africa. The possibilities are many, but the end result will be the same. Dead wedding revelers are a repetitious certainty. If you wait, the corpses of brides and grooms (or, as the New York Post put it, “Bride and Boom!”) will come. Over the years, according to the tabulations of TomDispatch, U.S. planes and drones have knocked off at least eight wedding parties in three countries in the Greater Middle East (Iraq, Afghanistan, and Yemen) and possibly more, with perhaps 250 revelers among the casualties.

And here’s a drone headline variant you’re guaranteed to see many times in the years to come: “U.S. drone kills top al-Qaeda/ISIS/al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula/[terror group of your choice] leader” — with the obvious follow-up headlines vividly illustrated in Andrew Cockburn’s new book, Kill Chain: The Rise of the High-Tech Assassins: not the weakening but the further strengthening and spread of such organizations. And yet the White House is stuck on its drone assassination campaigns and the effectiveness of U.S. air power in suppressing terror outfits. In other words, air and drone campaigns of this sort will remain powerful tools not in a war on terror, but in one that creates terror with predictable headlines assured.

2. Latest revelation indicates that FBI [NSA, CIA] surveillance of Americans far worse than imagined: Talk about no-brainers. Stories of this sort appear regularly and, despite a recent court ruling that the NSA’s mass collection of the phone metadata of Americans is illegal, there’s every reason to feel confident that this will not change. Most recently, for instance, an informant-filled FBI program to spy on, surveil, and infiltrate the anti-Keystone XL Pipeline movement made the news (as well as the fact that, in acting as it did, the Bureau had “breached its own internal rules”). In other words, the FBI generally acted as the agency has done since the days of J. Edgar Hoover when it comes to protest in this country.

Beneath such reports lies a deeper reality: the American national security state, which has undergone an era of unprecedented expansion, is now remarkably unconstrained by any kind of serious oversight, the rule of law, or limits of almost any sort. It should be clear by now that the urge for ever more latitude and power has become part of its institutional DNA. It has already created a global surveillance system of a kind never before seen or imagined, not even by the totalitarian regimes of the last century. Its end goal is clearly to have access to everyone on the planet, Americans included, and every imaginable form of communication now in use. There was to be a sole exception to this blanket system of surveillance: the official denizens of the national security state itself. No one was to have the capacity to look at them. This helps explain why its top officials were so viscerally outraged by Edward Snowden and his revelations. When someone surveilled them as they did others, they felt violated and deeply offended.

When you set up a system that is so unconstrained, of course, you also encourage its opposite: the urge to reveal. Hence headline three.

3. FBI [NSA, CIA, DIA, or acronym of your choice] whistleblower charged by administration under the Espionage Act for revealing to reporter [any activity of any sort from within the national security state]: Amid the many potential crimes committed by those in the national security state in this period (including torture, kidnapping, illegal imprisonment, illegal surveillance, and assassination), the record of the Bush and Obama administrations is clear. In the twenty-first century, only one act is a crime in official Washington: revealing directly or indirectly to the American people what their government is doing in their name and without their knowledge. In the single-minded pursuit and prosecution of this single “crime,” the Obama administration has set a record for the use of the Espionage Act. The tossing of Chelsea Manning behind bars for 35 years; the hounding of Edward Snowden; the jailing of Stephen Kim; the attempt to jail CIA whistleblower Jeffrey Sterling for at least 19 years (the judge “only” gave him three and a half); the jailing of John Kiriakou, the sole CIA agent charged in the Agency’s torture scandal (for revealing the name of an agent involved in it to a newspaper reporter), all indicate one thing: that maintaining the aura of secrecy surrounding our “shadow government” is considered of paramount importance to its officials. Their desire to spy on and somehow control the rest of us comes with an urge to protect themselves from exposure. As it happens, no matter what kinds of clampdowns are instituted, the creation of such a system of secrecy invites and in its own perverse way encourages revelation as well. This, in turn, ensures that no matter what the national security state may threaten to do to whistleblowers, disclosures will follow, making such future headlines predictable.

4. Contending militias and Islamic extremist groups fight for control in shattered [fill in name of country somewhere in the Greater Middle East or Africa] after a U.S. intervention [drone assassination campaign, series of secret raids, or set of military-style activities of your choice]: Look at Libya and Yemen today, look at the fragmentation of Iraq, as well as the partial fragmentation of Pakistan and even Afghanistan. American interventions of the twenty-first century seem to carry with them a virus that infects the nation-state and threatens it from within. These days, it’s also clear that, whether you look at Democrats or Republicans, some version of the war-hawk party in Washington is going to reign supreme for the foreseeable future. Despite the dismal record of Washington’s military-first policies, such power-projection will undoubtedly remain the order of the day in significant parts of the world. As a result, you can expect American interventions of all sorts (even if not full-scale invasions). That means further regional fragmentation, which, in turn, means similar headlines in the future as central governments weaken or crumble and warring militias and terror outfits fight it out in the ruins of the state.

4. Contending militias and Islamic extremist groups fight for control in shattered [fill in name of country somewhere in the Greater Middle East or Africa] after a U.S. intervention [drone assassination campaign, series of secret raids, or set of military-style activities of your choice]: Look at Libya and Yemen today, look at the fragmentation of Iraq, as well as the partial fragmentation of Pakistan and even Afghanistan. American interventions of the twenty-first century seem to carry with them a virus that infects the nation-state and threatens it from within. These days, it’s also clear that, whether you look at Democrats or Republicans, some version of the war-hawk party in Washington is going to reign supreme for the foreseeable future. Despite the dismal record of Washington’s military-first policies, such power-projection will undoubtedly remain the order of the day in significant parts of the world. As a result, you can expect American interventions of all sorts (even if not full-scale invasions). That means further regional fragmentation, which, in turn, means similar headlines in the future as central governments weaken or crumble and warring militias and terror outfits fight it out in the ruins of the state.

5. [King, emir, prime minister, autocrat, leader] of [name of U.S. ally or proxy state] snubs [rejects, angrily disputes, denounces, ignores] U.S. presidential summit meeting [joint news conference, other event]: This headline is obviously patterned on recent news: the announcement that Saudi King Salman, who was to attend a White House summit of the Gulf states at Camp David, would not be coming. This led to a spate of “snub” headlines, along with accounts of Saudi anger at Obama administration attempts to broker a nuclear peace deal with Iran that would free that country’s economy of sanctions and so potentially allow it to flex its muscles further in the Middle East.

Behind that story lies a far bigger one: the growing inability of the last superpower to apply its might effectively in region after region. Historically, the proxies and dependents of great powers — take Ngo Dinh Diem in Vietnam in the early 1960s — have often been nationalists and found their dependency rankling. But private gripes and public slaps are two very different things. In our moment, Washington’s proxies and allies are visibly restless and increasingly less polite and the Obama administration seems strangely toothless in response. Former President Hamid Karzai in Afghanistan may have led the way on this, but it’s a phenomenon that’s clearly spreading. (Check out, for instance, General Sisi of Egypt or Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel.) Even Washington’s closest European allies seem to be growing restless. In a recent gesture that (Charles de Gaulle aside) has no companion in post-World War II history, England, Germany, and Italy agreed to become founding members of a new Chinese-led Asian regional investment bank. They did so over the public and private objections of the Obama administration and despite Washington’s attempts to apply pressure on the subject. They were joined by other close U.S. allies in Asia. Given Washington’s difficulty making its power mean something in recent years, it’s not hard to predict more snubs and slaps from proxies and allies alike. Fortunately, Washington has one new ally it might be able to count on: Cuba.

6. Twenty-two-year-old [18-year-old, age of your choice] Arab-American [Somali-American, African-American or Caucasian-American convert to Islam] arrested for planning to bomb [drone attack, shoot up] the Mall of America [Congress, the Empire State Building, other landmark, transportation system, synagogue, church, or commercial location] by the FBI thanks to a Bureau informer: This is yet another no-brainer of a future headline or rather set of headlines. So far, just about every high-profile terror “plot” reported (and broken up) in this country has involved an FBI informer or informers and most of them have been significantly funded, inspired, or even organized by that agency right down to the fake weaponry the “terrorists” used. Most of the “plotters” involved turned out to be needy and confused losers, sometimes simply hapless, big-mouthed drifters, who were essentially incapable, whatever their thinking, of developing and carrying out an organized terror attack on their own. There are only a few exceptions, including the Boston Marathon bombing of 2013 and the Times Square car bombing of 2010 (foiled by two street vendors).

What the FBI has operated in these years is about as close as you can get to an ongoing terrorism sting-cum-scam operation. Though Bureau officials undoubtedly don’t think of it so crudely, it could be considered an effective part of a bureaucratic fundraising exercise. Keep in mind that the massive expansion of the national security state has largely been justified by the fear of one thing: terrorism. In terms of actual casualties in the U.S. since 9/11, terrorism has not been a significant danger and yet the national security state as presently constituted makes no sense without an overwhelming public and congressional fear of terrorism. So evidence of regular terror “plots” is useful indeed. Publicity about them, which runs rampant whenever one of them is “foiled” by the Bureau, generates fear, not to say hysteria here, as well as a sense of the efficiency and accomplishment of the FBI. All of this ensures that, in an era highlighted by belt-tightening in Washington, the funds will continue to flow. As a result, you can count on a future in which FBI-inspired/-organized/-encouraged Islamic terrorism is a repeated fact of life in “the homeland.” (If you want to get an up-close-and-personal look at just how the FBI works with its informers in the business of entrapping of “terrorists,” check out the upcoming documentary film (T)error when it becomes available.)

7. American lone wolf terrorist, inspired by ISIS [al-Qaeda, al-Shabab, terror group of your choice] videos [tweets, Facebook pleas, recordings], guns down two [none, three, six, other number of] Americans at school [church, political gathering, mall, Islamophobic event, or your pick] before being killed [wounded, captured]: Lone wolf terrorism is nothing new. Think of Timothy McVeigh. But the Muslim extremist version of the lone wolf terrorist — and yes, Virginia, there clearly are some in this country unbalanced enough to be stirred to grim action by the videos or tweets of various terror groups — is the new kid on the block. So far, however, among the jostling crowds of American lone mass murderers who strike regularly across the country in schools, colleges, movie theaters, religious venues, workplaces, and other spots, Islamic lone wolves seem to have been a particularly ineffective crew. And yet, as with those FBI-inspired terror plots, the Islamic-American lone wolf turns out to be a perfect vehicle for creating hysteria and so the officials of the national security state wallow in high-octane statements about such dangers, which theoretically envelop us. In financial terms, the lone wolf is to the national security state what the Koch Brothers are to Republican presidential candidates, which means that you can count on terrifying headlines galore into the distant future.

8. Toddler kills mother [father, brother, sister] in [Idaho, Cleveland, Albuquerque, or state or city of your choice] with family gun: Fill in the future blanks as you will, this is a story fated to happen again and again. Statistically, death-by-toddler is a greater danger to Americans living in “the homeland” than death by terrorist, but of course it raises funds for no one. No set of agencies broadcasts hysterical claims about such killings; no set of agencies lives off of or is funded by the threat of them, though they are bound to be on the rise. The math is simple enough. In the U.S., ever more powerful guns are available, while “concealed carrying” is now legal in all 50 states and the places in which you can carry are expanding. Well over 1.3 million people have the right to carry a concealed weapon in Florida alone, and a single lobbying group in favor of such developments, the National Rifle Association, is so powerful that most politicians don’t dare take it on. Add it all up and it’s obvious that more weapons will be carelessly left within the reach of toddlers who will pick them up, pull the trigger, and kill or wound others who are literally and figuratively close to them, a searing life (and death) experience. So the future headlines are predictable.

9. President claims Americans are ‘exceptional’ and the U.S. is ‘indispensible’ to the world: Lest you think this one is a joke headline, here’s what USA Today put up in September 2013: “Obama tells the world: America is exceptional”; and here’s Voice of America in 2012: “Obama: U.S. ‘the one indispensible nation in world affairs.'” In fact, it’s unlikely a president could survive politically these days without repetitiously citing the “exceptional” and “indispensable” nature of this country. Recently, even when apologizing for a CIA drone strike in Pakistan that took out American and Italian hostages of al-Qaeda, the president insisted that we were still “exceptional” on planet Earth — for admitting our mistakes, if nothing else. On this sort of thing, the Republicans running for president and that party’s war hawks in Congress double down when it comes to heaping praise on us, making the president’s exceptionalist comments seem almost recessive by comparison. In fact, this is a relatively new phenomenon in American politics. It only took off in the post-9/11 era and, as with anything emphasized too much and repeated too often, it betrays not strength and confidence but creeping doubt about the nature of our country. Once upon a time, Americans didn’t have to say such things because they seemed obvious. No longer. So await these inane headlines in the future and the repetitive litany of over-the-top self-praise that goes with them, and consider them a way to take the pulse of an increasingly anxious nation at sea with itself.

And mind you, this is just to scratch the surface of what’s predictable in the American future. I’m sure you could come up with nine similarly themed headlines in no time at all. It turns out that the key to such future stories is the lack of a learning curve in Washington, more or less a necessity if the national security state plans to continue to gain power and shed the idea that it is accountable to other Americans for anything it does. If it were capable of learning from its actions, it might not survive its own failures.

Tom Engelhardt is a co-founder of the American Empire Project and the author of The United States of Fear as well as a history of the Cold War, The End of Victory Culture. He is a fellow of the Nation Institute and runs TomDispatch.com. His latest book is Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Book, Nick Turse’s Tomorrow’s Battlefield: U.S. Proxy Wars and Secret Ops in Africa, and Tom Engelhardt’s latest book, Shadow Government: Surveillance, Secret Wars, and a Global Security State in a Single-Superpower World.

Copyright 2015 Tom Engelhardt

Blaming the US for Trouble in the Middle East Is Simply a Stretch

Last week a respected friend and colleague sent me an email making the standard claims about how all the problems in the Middle East are the result of imperial borders, colonialism, and US foreign policy. It’s the “blame the US” refrain. If you believe the West is responsible for ISIS and Middle East violence then you are easily manipulated by the Islamic state into believing just what they want you to believe. Sure, there is much to criticize about colonialism but borders are not so central to contemporary problems. Let’s take up the case of Iraq (for additional reading go to an article in The Atlantic available here). The three provinces of Iraq – Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra – were historically treated as the one area (called Mesopotamia) and Iraq’s eastern border with Iran dates back to the early Ottoman Empire. The boundaries of Iraq are not so arbitrary. Interestingly, the country with some of the newest Western carved out borders is Jordan and it is the more stable country as a result of King Abdullah.

Last week a respected friend and colleague sent me an email making the standard claims about how all the problems in the Middle East are the result of imperial borders, colonialism, and US foreign policy. It’s the “blame the US” refrain. If you believe the West is responsible for ISIS and Middle East violence then you are easily manipulated by the Islamic state into believing just what they want you to believe. Sure, there is much to criticize about colonialism but borders are not so central to contemporary problems. Let’s take up the case of Iraq (for additional reading go to an article in The Atlantic available here). The three provinces of Iraq – Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra – were historically treated as the one area (called Mesopotamia) and Iraq’s eastern border with Iran dates back to the early Ottoman Empire. The boundaries of Iraq are not so arbitrary. Interestingly, the country with some of the newest Western carved out borders is Jordan and it is the more stable country as a result of King Abdullah.

We fool ourselves into believing that how the Middle East was carved up after World War I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire is responsible for all the problems. Did you ever ask yourself what it is about a political culture that allowed extremism to take root in the first place! I can give you five explanations for the spread of fundamentalist violence and jihadism. The answers to these issues are always complex, and surely the United States is not completely innocent, but the list below better captures the realities of the political system that absorbs extremism.

- It is not a stretch, and an easy connection to make, when one blames so many leaders in the Middle East who failed to deliver a semblance of prosperity and freedom. Countries like Egypt modeled their secular world on the Soviet Union rather than Western market economies and have paid the price ever since.

- Political participation is one of the last things authoritarian leaders want so they have encouraged citizens to take solace in mosques. Consequently religion and the language of religion is the most common currency. Saudi Arabia has directly supported the fundamentalist Wahhabi strand of Islam.

- Ruling elites must give up something and guide the transition to democracy and open economies, but they have failed to do so in many places. Elites are crucial for the transition to modern political systems.

- The Middle East has lived by oil and will die by oil. An economy based on one resource is doomed to fade away in time but for now provides tremendous wealth to some but not others. The Gulf economies have failed to develop in certain economic areas and once again Islam stepped in as a refuge. The work of diversifying economies has yet to be done.

- Finally, the Muslim confrontation with modernity has partially damaged the culture rendering it less able to adapt and once again reinforcing religion as the common identity binding language.

It’s natural to look for explanations for things but reducing the violence, and confusion, and complexity of the collection of countries in what we call the Middle East to American foreign policy or humiliations is not very productive.

ISIS, which probably constitutes the most stable future threat, was created by all sorts of forces very few of which are rooted in US foreign policy. An excellent reading on this matter is “Who is to blame for the rise of ISIS?” It explains how the Iraqi Army has failed to defend borders and people; the Iraqi people have not challenged ISIS sufficiently; Nouri Al-Maliki the leader of Iraq failed to put together a majority power-sharing government; and even premature troop withdrawal is partially the blame for the rise in ISIS’s power.

In the end, ISIS came to power because individuals made the choice to adopt and support the movement. They chose violence over reconciliation. The vile quality that allows ISIS to consider itself murderously superior is well enough understood in history and social scientifically. Western democracies such as the US are not primarily responsible for the creation of ISIS, but will certainly have to play a major role in its elimination.

What Kind of Mentality Kills Teenagers Because They are Jewish or Palestinian? I’ll Tell You What Kind.

You have to be pretty far outside the category of “human” to kidnap three scared teenagers and shoot them in the back of a car. Shoot them for no reason other than they fit the category of “other.” The murder of Naftali Frenkel and Gilad Shaar, both 16, and Eyal Yifrach 19, and the Palestinian Mohamed Abu Khdeir reveals the monstrosity that can arouse itself in humans whenever group membership is highly salient and fueled by powerful beliefs such as religion. Let me explain how framing a conflict can be murderous.

Experts talking to lay people usually make the point that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not about religion or culture but land and national rights. It is a conflict between national political movements – Zionism and Palestinian nationalism – and perhaps includes broader Arab nationalism. Framing the conflict this way is actually quite good and beneficial. In addition to the practical implications, describing the conflict as one between two national political movements makes the conflict more amenable to management and resolution with all of the attendant rational and political bargaining. It implies sensible trade-offs and compromise along with future relationships and the positive attitudes and beliefs that will accompany these compromises and future relationships. Each side will broaden its circle of humanity and slowly include more of the other.

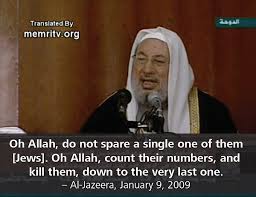

But with the integration and the unity government formed between Hamas and Fatah, not to mention the Hamas Charter and its aggressive religious history, we have a powerful religious element introduced. Islamizing the conflict is our worst nightmare and begins from the simple category definition of the conflict as one between two rival religions Islam and Judaism. Or, to put it in even more intractable terms, a conflict between two opposing absolutes. Now attitudes about the other are not subject to rational trade-offs and the anticipation of future relationships. And yes, the conflict can be Judiazed but there are important differences which we will take up at another time. This post is mostly about Islamizing the conflict. I will deal with revenge later.

Turning the conflict into a religious one between Islam and Judaism means you operate with only two categories – the ingroup and the outgroup with all of the biases and mental distortions that demonize and dehumanize the outgroup and wildly exaggerate the truth of the ingroup.

The murderers of these teenagers did not see human beings, they did not see naïve young boys, and they certainly did not see three individuals who like sports, school, and their friends. No, they saw three Jews or a Palestinian who are all alike; they saw the “other” who was responsible for usurping the holy land; they saw grossly distorted historical monsters who – as the Hamas Charter indicates – were a demonic force on earth, bloodsuckers and the killers of prophets.

And it’s getting worse. As Hamas asserts itself Judaism becomes its primary enemy. The hate and narrowing categories of acceptance will reach hallucinogenic proportions as Jews are described in demonic terms and according to the Hamas Charter are a “corruption on earth.” It will be increasingly easier to kill innocent teenagers because Islamizing the conflict drained them of any remnant of humanity.

The Hamas Charter – and I encourage everyone to read it to fully appreciate the depths of its depravity – relies on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The old charges of the Jews controlling everything would be laughable if they were not so consequential. Hamas is not bargaining over land because Palestine is sacred and not subject to division or occupation by anyone else. There will be no discussion of borders, or settlements, or land swaps. Palestine is dar al-Islam (the abode of Islam).

Islamizing the conflict is the worst thing that can happen from a contemporary social science and intergroup conflict point of view. It will increase the distance and differences, and decrease opportunities for positive contact even more than they are. As the two groups retreat into their own worlds and formulate their psychological and communicative categories such formulations will be increasingly based on misinformation, distortions, historical inaccuracies, stereotypes, and emotions until the two groups retreat to their respective corners each having drained the other of even the slightest consideration. At that point it becomes easy to murder teenagers.

Islamic and Western Approaches to Peace

Whether your intellectual tradition is that of the Enlightenment, or the religious patterns of Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, or Judaism along with modern liberalism each provides horizons of meaning that offer a picture and a future of peace. All of these intellectual systems have an end state that is, if not utopian and glorious, at least peaceful and orderly. But how do we begin to interrogate and engage these systems? What do we have to know about the cultures that are most representative of these belief systems?

In the micro world of interpersonal relations, or the more detached pedagogical stance one can take in the classroom, it is easy enough to make references to cultural generalities. We talk quite prolifically about cultural differences and enjoy citing examples of cultural variation. But when it comes to defending these cultural generalities, when one is asked to stand up in front of an audience and say things that involve generalities about cultures to which we do not belong, things get a little bit more difficult. I have participated in many conversations where generalities about culture were invoked (and I’m not talking about humorous stereotypes) but the participants would be hard-pressed to defend these generalities; they shy away from expressing cultural descriptions because they realize that such generalities are always a little bit on shaky grounds.

But on the other hand, there are characteristic qualities of cultures. We classify cultures as either individualistic or collective, self oriented or other oriented, modern or traditional, along with any number of other descriptions. These generalities often have some claim to legitimacy but they also are rarely a universally valid framework. We have to grapple with differences and try to avoid shallow cultural blather but at the same time improve the depth of our knowledge about cultures, especially cultures in conflict trying to resolve differences. Below, and in the next few posts, I explore some differences we might claim separate Islam from the West with respect to concepts of peace and conflict resolution. A good reading on this topic is Islamic Approaches to Peace.

When it comes to understanding Islam and its conceptions of peace and conflict management, we are in a difficult historical period because of “Islamism” and it’s narrow and aggressive discourse that is seen as a threat to peace. The concept of peace in the Islamic culture is typically misrepresented or ignored. But there are differences between Western and Islamic concepts of peace that must be understood. The differences between the two cultures form the basis for dialogue and deliberation. Yet, you actually see very little contact and very little theorizing about Islamic-Western dialogue. There are any number of reasons for this, but one of the most pertinent is that Western literature is more concerned about stating differences rather than commonality, and emphasizing the incompatibility of Islam with Western ideas about conflict.

There is a shameful lack of contact between Islam and the West with relatively little grassroots dialogue. There is a need for a new attitude and framework in order to organize knowledge about Islam for Westerners and organize knowledge about the West for Muslims. For example, there does seem to be a tendency to define Western approaches to conflict resolution as the “norm” or the ideal to strive for. We simply don’t have attitudes that expect Islam to be serious about peace. And although everyday contact between Muslims and Westerners is fine wherever it is possible (e.g. educational institutions), it still falls short of the structured and guided form of communication that results from dialogue and deliberation.

It is commonly accepted among conflict scholars that peace between deeply divided groups requires a global conception of peace that is integrated; in other words, problems will not be solved on the basis of narrow self-interest or the belief in one’s own cultural superiority with respect to ideas about peace. Peace will not come and problems will not be solved on the basis of a single dominant cultural attitude. Religion, for example, is essential to the attitudes about peace for Muslims but far less important for the secular West. And it is the West that must accept the role of religion and integrate it into the process.

All major religious, philosophical, and secular systems of belief and knowledge claim that peace will be the result of the full expression and recognition of the systems. And in a new world where boundaries are more porous and once separated groups must now confront the other there is an even more profound need for intercultural communication.