Blog Archives

Educating for Free and Deliberative Speech

Hearing criticisms of your own convictions and learning the beliefs of others are training for life in the multi-faith society. Preventing open debate means that all believers, including atheists, remain in the prison of unconsidered opinion. The right to be offended, which is the other side of free speech, is therefore a genuine right. True belief and honest doubt are both impossible without it. John O’Sullivan

I have been a pretty standard liberal Democrat all my life, but recently I have been more critical of the left’s retreat from First Amendment protections. I’m talking about the left’s willingness to restrict symbolic expression that is critical of an ethnopolitical group or identity group of any kind. A recent article by John O’Sullivan in the Wall Street Journal takes up the issue of the new limits on free expression in the name of protecting religious and ethnopolitical group sensitivities. The article is an excellent treatment of these issues and I highly recommend it.

I have been a pretty standard liberal Democrat all my life, but recently I have been more critical of the left’s retreat from First Amendment protections. I’m talking about the left’s willingness to restrict symbolic expression that is critical of an ethnopolitical group or identity group of any kind. A recent article by John O’Sullivan in the Wall Street Journal takes up the issue of the new limits on free expression in the name of protecting religious and ethnopolitical group sensitivities. The article is an excellent treatment of these issues and I highly recommend it.

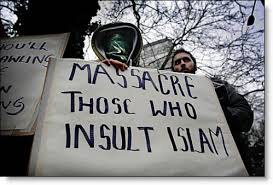

The harsh and anti-democratic strand of jihadist Islam has successfully scared enough people into restraining free expression in the form of restricting criticism of religion and political culture. Earlier in the history of free expression, O’Sullivan explains, the predominant restrictions on speech were with respect to obscenity, pornography, and language that was sexually explicit. The purveyors of these restrictions were moralistic and believed themselves to be defending proper standards of society. Political speech was strongly protected. But now, the calls for restrictions are designed to limit the political speech of others and consider off-limits the entire array of topics surrounding religion and politics. Obscene and pornographic speech was limited on the basis of protecting the broad moral foundation of the culture, limiting speech that is critical of religion is justified on the basis of particular groups with each making their own demands.

Burning an American flag is considered political speech and symbolic expression that is protected. I can legally burn the American flag in the center of the town square as a symbolic statement of opposition to some aspect of American foreign policy. But if I burn the Koran, which would still be legal in the United States as politically protected expression, it will cause a different reaction. There is a suggestion that the US endorse an international blasphemy law that would define the Koran as so special that burning it constitutes a particular offense, rather than simply protected symbolic expression.

The traditional approach to protected speech is to ignore the content of speech but simply disallow symbolic expression that will cause imminent danger (yelling “fire” in a crowded theater).Yet feeling free to limit speech because words are supposedly so powerful and dangerous is a slippery slope that will slowly erode freedom.

The Answer: Education

One does not come into the world with established political ideology and sensitivities to managing group differences. Democracy and freedom of speech is advanced citizenship in a democracy and must be taught. Free and open societies, where citizen participation is rich and required, necessitate learning the habits of pluralism and democratic processes. The legal environment surrounding freedom of expression has drifted toward an oversensitivity to categorize speech is injurious and in constant need of management. We should not be in the business of restricting all sorts of pure symbolic behavior. Living amongst one’s fellows in a pluralistic, multi-faith, diverse environment requires living in a world that is not of one’s own making and is constituted by differences. These differences must be managed through the deliberative communication process which is by definition “contestatory.”

The lines and distinctions implied here are difficult. For example, do we allow street gangs to deface public buildings with racist slogans and call it “freedom of expression”? I presume it would be possible to define such activities as sufficiently harmful and capable of producing imminent danger, but it will depend on many factors. Slow and long term as it is democratic cultures must continue civic education that includes democratic values.

Power to the People! A Call for Citizen Engagement in Israel Palestine

I’ve got an idea that is not really so bold as much as it is ignored. My idea responds to what I consider to be a weakness in the political considerations that characterize the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. And that weakness is the failure of sufficient input from the general populace. I mean meaningful input taken seriously. Polls in both Israel and Palestine indicate that upwards of 60% of the population wants peace and find the two state solution to be sensible. It is true, according to a new poll of Palestinians, that the two state solution is falling away in popularity. But it can be reinvigorated and it does represent something the Palestinians support. A few people (e.g. Hamas, settlers, elites) cause a lot of problems and their messages are sometimes confused with consensus. Moreover, political elites cannot always be trusted and are subject to their own strategic manipulations. We’ve seen nothing but failure in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict even though it has been characterized by diplomatic influences.

In spite of all the political contact between the two sides the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is mired in complexity partially because the approach to peace building is not sufficiently multifaceted or inclusive of popular consciousness. Any sort of “people-to-people communication” can improve grassroots contact between the two sides, build coalitions, and engage ordinary citizens. But these forms of contact must also bubble up to influence political leaders.

I’m calling for groups of Palestinians and Israeli Jews to organize themselves into participatory groups characterized by democratic mechanisms that parallel the spread of recent nondemocratic dynamics. There are five other qualities that should be descriptive of these groups: first, these groups should be deeply integrated into the various communities; participants should be representative of the population, not elites. Two, these groups must be interdependent such that what happens in one group influences another group. Borders, population characteristics, and security matters are examples. Three, these groups have to be repeated often enough to discover consistent patterns that represent defensible conclusions. Four, they must be governed by principles of deliberation – some of which are discussed below – and democratic and public sphere criteria are expected. Finally, these groups must produce some sort of product and make it available to the public, which should be following the discussions anyway.

I do not intend for these groups to be revolutionary. They are grassroots movements designed to achieve a sustained message that typifies as much as possible population sentiments. The gap between public opinion and the perspective of the elected elites should be closed or constrained. The goal is to drive a reform agenda that improves the relationship between the populace and the government. These discussions should be as open and public as possible with the media performing their best function as a megaphone that reaches broad populations. The meetings should perform a legitimizing function and help find a path leading to some productive solutions.

Participatory Democracy

There are more models and procedures for citizen participation then we can respond to here (click here for a description six models of citizen participation), but a standard model of participatory democracy is best. This is a general term that refers to democratic procedures and representative decision-making. That is, nonelected citizens have decision-making power and the communication within these groups empowers individuals and promotes their cooperation. Participatory democracy is a model for social justice and the relationship between civil society and the macro political system.

It is true that participatory democratic discussions are historically idealistic and can be abstract but there are a number of success stories and advantages under certain circumstances. Organizing such groups is not easy and requires political will but it remains a relatively unexplored avenue. Finding a pathway to peace is a social construction that must include public debate and discussion. If these proposed participatory groups can establish themselves and maintain consistency they will be less vulnerable to the destructive influences of extremists on both sides. And managing these extremists – these few people who cause a lot of trouble – is particularly important in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict because these extremists will do anything to prevent productive solutions. Deep and widespread citizen engagement is probably necessary to build a foundation for a new political order that will be necessary if this conflict is going to be at least managed if not resolved.

There will be more on how to develop, organize, and structure these proposed public discussion in future posts.

Seeing Media Bias Everywhere Is Bad for Democracy – and Peace

There is a well-known study conducted in 1985 that ran a perfectly simple clean little experiment. One group favorable toward Israel and another group supportive of the Arabs were exposed to identical news stories about the violence in Lebanon in 1982. Even though both groups saw the same story, and all conditions of the experiment were the same, each believed the coverage was distorted and biased with respect to their own side; that is, they thought the media was hostile to their side. This is termed “the hostile media effect” and it very simply refers to the tendency to prefer your own group (either pro-Israel or pro-Arab) and distort perceptions of an “out” group and thus believe that the media are hostile to your side but lenient and supportive of the other side.

There is a well-known study conducted in 1985 that ran a perfectly simple clean little experiment. One group favorable toward Israel and another group supportive of the Arabs were exposed to identical news stories about the violence in Lebanon in 1982. Even though both groups saw the same story, and all conditions of the experiment were the same, each believed the coverage was distorted and biased with respect to their own side; that is, they thought the media was hostile to their side. This is termed “the hostile media effect” and it very simply refers to the tendency to prefer your own group (either pro-Israel or pro-Arab) and distort perceptions of an “out” group and thus believe that the media are hostile to your side but lenient and supportive of the other side.

Given the orgy of news coverage surrounding the war in Gaza, and the inevitable outcry about media bias, I thought I would clarify some distinctions and explain the social scientific foundation of media bias. More journalists and reporters work more diligently to present a balanced view of the conflict then the public gives them credit for. But the same journalists will tell you that their good efforts to be balanced are for naught and they are flooded with mail claiming bias regardless of what they do. This tells you that the bias probably comes from the consumer of the message rather than the producer.

The general tendency to see bias is common enough. One of the most well-established relationships is between message distortion and group identity. If you sort people into two groups (e.g. Israelis-Palestinians) this immediately sets into motion a series of processes that influence how messages are interpreted. And, these interpretations always favor one group or another including interpreting messages as biased against their own side. The results of the 1985 study referred to earlier have been replicated with numerous topics and events. We prefer to think of ourselves as treating people equally or respecting diversity of all sorts but the truth is we strongly identify with groups and define ourselves according to group membership.

From a rather straightforward evolutionary perspective, any exposure of your ingroup to negative information is perceived as a potential threat. This stimulates our sense of self protection, which takes precedence over other cognitive processes, and causes us to question the nature and quality of the information. Claiming that the media are biased against us or the information is substandard allows group members to minimize the inconsistency between their group favorability and information inconsistent with maintaining their ingroup status.

Moreover, the more one intensely identifies with their group – such as a religious group or ethnic identity – the more individuals feel potential threat and the more intense is the relationship between group identity and sensitivity to information threats. These relationships are further intensified when group members consider their group to be particularly threatened or vulnerable. If you ask a strong supporter of Israel or a Palestinian whether or not they feel their group is vulnerable, or threatened, or disrespected they will certainly answer in the affirmative and consequently are more responsive than most to information threats.

There are of course numerous consequences to the distortion of perceptions and information resulting from group identity – sometimes deadly consequences – but the threat to democracy is a problem that receives less attention than psychological ones. There are three of them: one, the quality of information failure. Information is discounted or judged negatively sometimes when it should not be. It becomes difficult to find common information acceptable to both sides which is necessary for conflict resolution. Secondly, group identity distortions result in political polarization. The two sides of an issue see themselves as more extreme than they might actually be and retreat to more extreme positions which makes it even more difficult to manage problems. And third, the sense of being threatened or the recipient of hostile media attention creates conditions that justify more extreme or even violent behavior. The group considers its existence to be in jeopardy and this justifies more extreme behavior in the interest of “protecting themselves.” It is analogous to increasing constraints on civil rights in the face of terrorist activity.

How do we moderate group identity affects? We will pay some attention to that issue next week.

Syria As the Prototype for the Loss of Democratic Freedoms

In a recent Wall Street Journal article Puddington and Kramer reported that there has been a decline around the world in political rights and civil liberties as measured by Freedom House. True enough, the measurement of these things is not an exact science but Freedom House does a decent job of identifying key variables and definitions correlated with cultures that privilege democracy and civil liberties. After some years of improvement because of democratization around the world the general trends have been in decline. The authors report that 54 countries had registered declines in political rights and only 40 registered gains.

The reasons for these declines are interesting and the current conflict in Syria poses a particularly fitting example. The case of Syria is a typical model of authoritarianism that holds its power for a period of time through force and intimidation and then loses that power to violence and revolution (think Egypt, Tunisia, Libya). But even more interestingly the earliest mistakes are confusing violence with politics; that is, organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood or any other anti-government faction resorts to violence because there are no legitimate outlets of political expression and change. There’s a rather simple video you can watch which lays out the structure of the conflict in Syria and is actually a model for many other places. The video is brief and simple but is a template for any number of political situations. It is called “Syria explained in five minutes.” The decline in political freedoms is correlated with the political processes on display in the video.

Many of the losses of political freedom are associated with efforts to sabotage the Arab Spring. Religion and illiberal factions are reinforced for damaging democratic gains. And there is the very damaging influence of outside powers that imagine democratic gains as contrary to their own interests. Hence, countries like Russia, Iran, and Venezuela have conspired to keep Assad in power. Moreover, the Middle East is no longer the worst scoring region of the world when it comes to measurements of freedom. Russia has increased the intensity with which it silences groups, denies rights to nontraditional groups such as gays and lesbians, and uses its oil clout to interfere with any political process that is contrary to its interests. Russia cracks down on NGOs, civil rights activists, journalists, and any political opponent who poses a real challenge.

Russia, China, and Venezuela light the way for authoritarian governments that dominate media, security, as well as legislative and judicial branches of government. They do this mostly by blindly supporting centralized authoritarian governments such as the military government in Egypt or of course Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Syrian opposition to Assad is highly fractionated and is composed of the Free Syrian Army (deserters from Assad’s army), numerous Islamic groups from more extreme (e.g., “Battalion of Truth”,), to less extreme (Liwa al-Tawhid “Battalion of Monotheism”). There are Kurdish groups and independent groups not to mention attempts to form organizations that are more inclusive such as the “National Coalition.”

Clearly, the aggressiveness of extremist Islamic groups keep democratic pressures at bay and their presence in places like Syria will prevent democratization for a generation to come. And, finally, perhaps even more disturbing is the paralysis of places like the United States. We have said little and played an insignificant role in Syria because there’s no group to identify with and support. Secretary of State Kerry has worked to broker discussion at the macro level but the US is less engaged then countries like Russia and Iran. This can’t be good.

How Israel Can Be “Jewish”

This is a big and controversial issue and I will not satisfy most people. Moreover, it is steeped in serious issues related to political theory, culture, philosophy, and the law. Better minds than mine have grappled with this issue. Still, I’m going to make a case. I’m going to make a case for two reasons: one, I believe a defensible case can be made. And, secondly, I believe it is important to make the case because Israel is clearly deserving but vulnerable and its political status is important for its long-term prospects. Israel is besieged on all sides by those who see it as illegitimate and conceived in sin (a Christian image). For these reasons – along with historical and cultural connections to the land as well as the ethnopolitical character of the people –it is important to establish Israel as a Jewish state. The single best reading here is by Ruth Gavison titled “The Jews Right to Statehood: A Defense.”

For starters, a Torah state run by Orthodox rabbis is not only undesirable but not defensible. A legitimately recognized Jewish state must be as democratic as possible and founded on human rights. It’s important to recognize that Israel cannot be a liberal democracy in the same vein as the United States. I’ve made this argument before but it is simple enough: if Israel is going to be even slightly favorable towards Jewish particularity than it is going to privilege one group sometimes at the expense of others. We have to remember that democracy is a continuum.

If some secular professor representing the universal values of the contemporary left believes that any state organized around ethnicity or religion is a remnant of ancient tribalism and thus undeveloped, then I say “so what?” The type of state I have in mind is not a theocracy. It is a state that privatizes much of religion but simply works to fulfill, support, and express the religious culture of Judaism. For example, Israel has no religious test for its highest offices of president or prime minister. The president or Prime Minister does not have to be Jewish in the religious sense he or she just has to have the fulfillment of the Jewish state in mind. They have to accept the founding principles of doing nothing to interfere with the Jewish character of the state.

We can dispense with the criticism of Israel as a political entity from Muslim states quite easily. Many of them (Oman, Qatar, Kuwait) have Islam as the religion of the state and laws requiring public officials to be Muslims. This is fine, it is a principled point but certainly lends hypocrisy to the claim that Israel should be multicultural or one secular state. Their refusal to acknowledge Israel as a Jewish state is not a political or philosophical argument, it is a charged political ideal based in their refusal to make peace with Israel.

And there are examples of secular states with religious ties that operate quite well. I would compare something proposed for Israel to that of Denmark. In Denmark the Constitution recognizes “the Evangelical Lutheran Church” as the established Church of Denmark. The only requisite is that the political leadership in Denmark do nothing to interfere with the established church.

Israel must continue to establish justification on moral universal grounds as much as possible because this appeals to most of its own people who feel the power of the Zionist project but are not particularly religious. Gavison makes the interesting point that the more Israel argues on the basis of universal values the more the Palestinians will follow suit rather than claiming ownership based on the sanctity of Muslim lands. The state of Israel will be a contestatory political system constantly engaging in interaction designed to balance human rights with its Jewish nature. This is consistent with all democracies who rely more on argument and deliberation than ideology.

I reiterate that it will be impossible for Israel to be absolutely neutral with regard to cultural, ethnic, and religious issues. There will be differences in civic equality. But these differences do not have to be fatal. It is still possible to have a democratic Jewish state that respects the rights of citizens – and certainly allows them to engage in their own religion in the same way as the United States does not interfere with religious practice as long as it is in the private sphere – and still represents a national identity.

So for now, the state I am imagining is not completely neutral, has an official language that is Hebrew, a calendar that marks Jewish time (including Shabbat ofcourse), and puts forth a public culture that is Jewish. The public sphere will be important in the Jewish state because that is the context for contestation with respect to issues that affect the public in general. People will be able to practice Judaism or any religion but the management and compromise will come in the public sphere when one person’s rights have to be balanced against another’s.

The state will be as democratic as possible and proudly Jewish.

I will say more next week.

What It Means for the State of Israel to Be “Jewish”

In a couple of posts I’m going to explore the issue of an official “Jewish” definition of Israel. I’m going to explore the issues and expose the difficulties and suffer the different philosophical consequences including the conundrums, logical impossibilities, and damning inevitabilities. Then I’m going to conclude that Israel should be Jewish, that the entire history of the country and the Zionist project makes little sense if Israel is not “Jewish.” You will see, of course, that according to some I’m recommending “Jewish lite” and that will be enough to disqualify my conclusions. But ultimately there’s only one way to meet that goal of Israel being both Jewish and operational and that’s for the Judaism to inform the state but not control it.

This question of Israel’s Judaism is really no small matter because it determines whether or not the state serves Judaism or Judaism serves the state. In other words, if the state is Jewish first and democratic second then the democracy has to be flexible enough to fit the Jewish nature of the state. Strongly religious Jews who want Israel to be a Jewish state begin with Judaism and shape all other forms of government to fit the needs of the Jewish community. Places like the United States begin with democracy and shape the society to fit the democracy. This is known as a liberal democracy and in the more pure sense is impossible in Israel if the state is “Jewish.” I would recommend a reading from the Jerusalem Center for Public affairs available here.

If Israel is devoted to Jewish particularity than it begs the question about what that particularity is and whether or not it is sustainable. A society that is truly communal in the sense that everyone holds a religious or ethnic identity is a society that is truly actualized and expressed by the state. The “state” is truly a full expression of the people and not simply a compromise or the sum of the parts. Even at the risk of some exaggeration the state becomes the full expression of the nature of the people. Now, we’ve seen all this before and it certainly wasn’t pretty (think Fascism or the Soviet Socialist Republic). But it is not inevitable that the state will gravitate toward authoritarianism and oppression – even though constant monitoring is required. But Israel will have trouble if it has a strong sense of Jewish identity wrapped up in the state because the community is not cohesive. An officially Jewish Israel will be oppressive for non-Jewish groups such as the Arabs. Again, this is a situation that simply cannot stand. Israel must find a way to be Jewish but acceptably tolerant of the groups within its confines that are not Jewish. It is easy to describe the state as fundamentally expressing a culture when everyone in the culture is the same or holds the same political or religious values. But government is about managing differences and this is going to be true even of Jewish government.

So this is the primary tension. The tension is between Israel as a modern state and Israel as a continuation of Judaism. In what sense is Israel uniquely Jewish? Well, we could begin with the question of the Jewish people living independently in their own country. How important is it that Jews have a sense of completeness and does this depend on living in certain territory? An Orthodox Jew, although not all strands of orthodoxy, will tell you that the task of completing the Jewish people is dictated by God and an in-tact political system is a means to that end. In fact, the reconstitution of the state of Israel in the biblical and religious sense is a sign of the coming of the Messiah. In the Bible a collection of people make up the nation and they are permanent entity. In this image Israel would become a Torah state that might be an honorable expression of the will of Jews, but it would also be discriminatory not only against non-Jewish groups but include gender and the various intellectual discriminations. To be sure, Israel could create a state of the Jewish people and such a state would struggle in contemporary terms.

We are still confronted with the question of how modern Israel fits into the long tradition of Jewish civilization. And if we decide that Israel is Jewish first then there is the daunting question not of Judaism – which will make adjustments slowly to the modern world – but how Jewish Israel fits into the contemporary culture of justice and fairness for all. More later.

5 Barriers That Must Be Overcome for Islam to Move toward Democracy

Westerners who live in democratic countries usually have trouble imagining other forms of political systems. It’s sort of like most Americans who think that other people in the world would be American if they only had the chance. Extending such reasoning implies that most people believe that Muslims would be democratic if they only had a chance. And while such reasoning might be seductive, the road to democracy will be long and difficult. Here are some basic forces preventing the adoption of serious democratic conditions anytime soon: A good source for additional information is a book titled Islamic Democratic Discourse by M.A. Muqtedar Khan.

1. Democracy is relatively unrealistic for serious Muslim polities because of its emphasis on individualism and secularism and the almost idealization of these things. The basic Enlightenment principles of progress and a continuous movement toward a more free and truthful future is quite alien to Islam. Moreover, many Muslims are skeptical about the gap between the truth and the ideal of democracy. They believe the United States sells an appealing sounding tonic but its actual consumption is bitter.

2. Muslim societies are not oriented toward individualism and they are more attached to collectivist ideals and an authoritative text. Pushing a democracy agenda continues to impose models and values on Muslim societies that do not serve the needs of that society and are inconsistent with it. And pushing democracy results in a distraction for Muslims directing their attention away from the achievement of a genuine Islamic society. Some of the radical thinkers thought that it took time to achieve a genuine Muslim society and democracy interfered with that. These radical thinkers (such as Sayyid Qutb) were also more interested in returning to earlier idealized political organizations and clearly democracy is inconsistent with these historical periods.

3. Many Muslims, especially the traveling intellectual class, are “put off” by what they see in capitalist systems. They easily believe democracy is for the rich and is based in corruption, colonialism, and is a general anathema to Islam. And it is not difficult to find examples of all of these things even though it is an exaggeration and not particularly correct to assume that they are the definitional base of democracy. The sort of personal freedom that democrats value and cherish is seen by many Islamic intellectuals as resulting in corruption and social degradation, whereby moral standards slip away and prohibitions about sexual conduct and other behaviors are abandoned. Again, it is easy enough to find examples of these things and make the case. Some even take it a step further and conclude that the goal of democracy is to destroy Islam.

4. The West has tried to make the case that there is no serious contradictions between Islam and Western civilization namely democracy. But Muslims increasingly respond with statements of clear contradiction. For example, they explain that Muslim civilization is dependent on divine revelation and that life is directed toward religious fulfillment. By contrast, Western democratic societies are more rooted in materialism, secularism, and individuality. These things are quite distinct from Islamic spiritual and moral values. For Islam, science and reason are subject to the conditions of revelation and there is no separation of mosque and state.

5. Finally, some theorists compare the Muslim system of consultation in decision-making with democracy. But these two systems remain distinct enough such that democracy cannot be compared. Muslim decision-making is top-down and a sort of elitist consultation. It lacks the nitty-gritty interaction of the population. And the consultation system is typically more concerned with the proper interpretation of Islam than it is with civic jurisprudence. Shia sects have always been more preoccupied with the existence of a divine ruler than with democratic processes and this forms a barrier to change. In fact, these principles have become alternatives to democracy and interfered with many democratic influences. Democracy will have a tough time as long as the primary objective of the Islamic state is to implement divine law even if this law is interpreted by erudite men.

Muslims see themselves as essentially an ethical enterprise and not as an enlightened polity on its way to democracy. In fact, the intrusion of human discretion makes the implementation of divine commands more difficult. For the serious Muslim human development and law are unambiguously derived from Islamic sources. This makes democracy quite untenable.

Back to the Future for Egypt: They Have Returned to the 1950s

I’ve been skeptical about emerging democracies in the Middle East in general but Egypt in particular. There have been a few positive signs here and there and that is encouraging. Last week’s post was devoted to REAL democracies and, if I do say so myself, was a pretty convincing comparison of what even rudimentary democracies should look like and how places like Egypt do not measure up.

But I thought Walter Russell Mead’s article in the Wall Street Journal on the failure of our grand plans in the Middle East was particularly insightful. You can find the article here. In fact, I thought his main point about what actually happened with the takedown of Mubarak was so convincing that my dose of depression about Egypt’s supposed emerging democracy is on the increase. And although I’m not convinced of each point made by Mead, his analysis of the relationship between the military and the government is spot on. The military is a privileged organization in Egyptian society. The military leadership is an elitist segment of the society that garners significant benefits and perks, which they are not about to give up easily. Some of the strongest and most accomplished leaders in Egypt are military, and they move easily between the military and the civilian government. The military is highly integrated into Egyptian politics and considers itself the dominant and most important state institution.

It turns out, according to Mead, that Mubarak was trying to arrange for his son to be his successor and avoid altogether the military’s role in choosing a future leader. This would have turned Egypt into a family dynasty rather than a military republic. The military leadership was having none of this and was involved in fighting back partially by creating unrest. The military touted their democratic credentials by standing back and letting protest movements challenge Mubarak until he fell. They then stepped in and restored peace and quite skillfully played the father-protector role. Even though the military is more powerful than the Muslim Brotherhood, they accepted the appointment of Morsi initially believing they could manage him. When Morsi turned out to be less than competent and failed to understand his role the military removed him. Again, Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood credentials worked to his disadvantage since both the military and the general population is suspicious of the Brotherhood.

So, what do we have now! We have the Egypt in the 1950s. Egypt is a military republic that has come full circle and made no progress toward democracy. Mead continues to explain that the population assumes that only the military can protect them from the Islamists and hence maintain a sympathetic attitude toward the military. The other two forces in society – liberals and the Muslim Brotherhood – are fluttering in the background incapable of doing much.

Both Mubarak and the leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood are on trial which I presume will justify military political goals. Mubarak, who is from the military, was sentenced to life imprisonment but a retrial was ordered. This will allow the military to remove Mubarak but pay their debts to one of their own. The military has skillfully deposed Mubarak and appeased the population who would have revolted had they watched him walk away free, but the military will ensure that Mubarak’s final days are quiet and in the background.

Egypt is an important culture and strategic ally of the United States. A couple of years ago there was great hope and optimism for enlightened progress in Egypt. But such hope and optimism are waning. We have to sit back for a while and let Egypt stabilize before altering our foreign-policy stance. But we can’t sit back for too long because issues related to Iran, the peace treaty with Israel, Islamism, terrorism, and various strategic interests await us.

What It REALLY Means to Be a Democracy: Egypt Ain’t It.

I grow weary of listening to all these claims of developing democracies in places like Egypt, Tunisia, and Libya. It’s well enough understood that elections alone don’t mean much and some minor rabble rousing from the population is equally as trivial. I have little interest in pseudo-democracies, hybrid democracies, illiberal democracies, nondemocratic but liberal states, and societies where strands of democracy exist but must be upheld and supported by the military of all institutions.

A true democracy achieves consolidation and the best thing one can read on consolidated democracies is by Linz and Stepan (Journal of Democracy, 7, 1996). A REAL democracy, one that is established and fully functional, is a system of institutions and communication patterns that does not compete with anything else. Places like Egypt and Libya will be considered truly democratic when the current regimes no longer have to grapple with the problem of governmental breakdown. When the majority of people believe that any political change must only emerge through the democratic process, when there is no significant movement to control or overthrow the government, then democracy is taking hold in a culture.

In REAL democracies the actors do not spend their time trying to create nondemocratic processes. Certainly the military does not step in and remove someone from office. It is true that removal of an anti-democratic leader can be part of the transition to a genuine democracy, but this represents an early unstable stage of development not what I am calling a REAL democracy. In such democracies the population holds the belief that democratic institutions are the only way to govern and any support for an alternative system is small. Democracies remain a continuum from well-developed liberal democracies (the US, France) to lower quality pseudo-democracies (Venezuela, authoritarian groups democratically elected, e.g. Hamas). And these lower quality democracies are marked by the ease with which nondemocratic alternatives gain support.

REAL Democracies Have the Following Features:

First, the citizenry must be intellectually and politically developed such that they appreciate democratic institutions and support the role they play. An angry tribal citizenry, who might be more properly termed “subjects” than “citizens,” will have trouble meeting the standards of an educated citizenry who have the proper democratic habits of mind. Democracy is advanced citizenship and often runs contrary to the preference of many for quick and easy decisions. A democratic population requires a level of sophistication.

Secondly, you know that a democracy is stable when the society has an active and influential civil society. Still, a stable civil society is not enough. Egypt has benefited from it civil society because it is increasingly educated and demanding of democratic processes and market economies. The civil society must be able to create pressure on government and leadership; it should have the capacity to monitor government, and resist nondemocratic pressures.

The ability to provide citizens with what they want and actually “get things done” is a third quality of REAL democracies. The institutions and structures of government must be skilled and professional enough to carry out laws and regulate the political system. We are seeing now in Egypt the removal of elected political officials (the justification of which is debatable) and the military cracking down on a significant portion of the population. This is prima facie evidence that the institutions of government are not working in a democratic manner.

There are other important issues associated with genuine democracy (the legal system, the economic structure) but no other is probably as basic as the right of the public to contest policies and priorities. Democracy should not be composed of powerful ideological forces (e.g. the Muslim Brotherhood) whose goals are to absorb other groups; rather, the concept of the public sphere should be dominant – a place where representatives from any number of ideologies come together to work out problems that are shared by everyone. Public contestation is the foundation of the interactive system of argument and discussion that is the basis of governance.

Places like Egypt are trying to break free of cultural and political constraints and might be an interesting case of the “transition” to democracy, but do not yet represent REAL democracies.

Two Ways to Think about Egypt and the Birth Pangs of Democracy

We are in a very real sense witnessing Egypt’s struggle to shed the skin of authoritarianism and emerge as a democracy. One of the more important debates that accompany this struggle is just how democracies do emerge. Must they go through phases? Are certain cultures susceptible to authoritarianism and will never democratize? How long does it take? There is lively debate over these matters and I encourage anyone to read the Journal of Democracy (JOD).

Few people would question the value of democracy as a form of governance. In fact, it is on its way to becoming a universal value. It simply has tremendous advantages such as an outlet for conflict resolution, rarely waging war against one another, promoting privatization and economic development, and generally less likely to abuse its citizens. The thorny issues are still how we turn antiquated cultures into democratic ones. Some people stress preconditions such as economic development, equality, and certain cultural traits having to do with associational skills. Sheri Berman (Journal of Democracy, 18, 2007) offers an insightful summary of how democracies emerge. She explains how the “preconditionists” stress the importance of national prerequisites and others are “universalists” who claim that democracy can develop in many ways and be successful in diverse political environments. The “third wave” of democracy beginning in 1974 seemed to favor the “universalists” since dozens of countries with diverse cultural backgrounds made the transition.

Egypt seems to be one more domino falling into line after Tunisia, Libya, and Syria. The universalists are convinced that democracy can emerge anywhere and such an attitude prompted the United States incursion into Iraq and Afghanistan. We were convinced that we can plant the seeds of democracy and watch them grow in these alien soils. It remains to be seen just how naïve we have been. But more interesting, and related more directly to Egypt, is a new perspective by preconditionists who insist that a developmental path must be followed and places like Egypt have much to do to cultivate that path. Fareed Zakaria suggests there must be a tradition of liberalism for democracy to succeed. In the end, the march toward a stable democracy is long and slow but the best way to understand these transitions is to study the countries that have experienced them.

First of all, there is the matter of overthrowing authoritarian regimes and then the matter of replacing them with democracy. These are two different processes requiring two different sensitivities. The old order will desperately hold onto its privileges, and we are seeing some of that now with Egypt’s military. On the other hand, some theorists believe that a strong military and authoritarian government will lead to democracy faster than a weak and feeble semi-democracy. We’ll have to wait and see what direction the Egyptian military takes. Berman in her article mentioned above concludes that it is easier to bring down an authoritarian order then it is to replace it with a stable new one. That is probably a pretty safe conclusion.

In the end, the path to democracy is complex and neither the “preconditionists” or the “universalists” are completely correct. Democracy does not come into being peacefully and it does not emerge in a straight line. It is certainly true that political qualities such as freedom, prosperity, and tolerance both stimulate democratic sensibilities and are in turn developed as a result of democratic behavior. I’m afraid there are no easy answers for the Egyptians. They must undo an old order but put into effect a new one of which they have no experience. It is of little consequence to those living in Egypt now, but only future generations will bring new democratic opportunities to the Egyptians.