Is This Editorial Cartoon Funny?

People enjoy political cartoons. They make for fast iconic processing and cut to the quick of a point. This cartoon by Steve Bell is clearly cynical and anti-Israel. Its essential point is clear enough – that Israel values its own lives greater than that of the Palestinians. An even deeper and more cynical and insensitive interpretation would be that “only” three lives are considered more significant than all of the Palestinians.

People enjoy political cartoons. They make for fast iconic processing and cut to the quick of a point. This cartoon by Steve Bell is clearly cynical and anti-Israel. Its essential point is clear enough – that Israel values its own lives greater than that of the Palestinians. An even deeper and more cynical and insensitive interpretation would be that “only” three lives are considered more significant than all of the Palestinians.

But the cartoon does represent the mindset that characterizes the perception of Israel. On the one hand, any culture disproportionally prefers its own people and interpretations of its culture that are favorable. Why wouldn’t an Israeli, or an American, or member of any other culture be at least just a little biased towards its own people and political conditions? But this cartoon doesn’t state an obvious political reality; it’s not a simple statement of support and preference for one’s own that anyone can understand. No, it’s an indictment. It is a charge that Israel considers itself to be superior, that the lives of three teenagers (three coffins draped in an Israeli flag) are considered more important than all the Palestinian suffering.

Political cartoons that are rich in interpretive possibilities lend themselves to multiple issues and implications. This one not only accuses Israel of unfair and biased attitudes about human life but also speaks to the issues of moral superiority and moral equivalence. It accuses Israel of considering themselves to be morally superior, which is why the death of the three teens outweighs the Palestinian experience or the other side of the scale. And even though, as referred to above, this is common enough and true of any political culture in the hands of a cynical cartoonist it becomes an accusation. Moreover, as part of this bias towards one’s own group, there is the matter of moral equivalence or the belief that your own group is equally as justified as any other group. If the killing of the three teenagers was the act of a crazed individual (such as in the case of Baruch Goldstein) then that is different than it being a political act. But if Hamas for example consciously planned to kidnap and kill three Israeli kids coming home from school as part of a political statement, then an aggressive response is justified.

One of the most pernicious aspects of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is the sense of moral equivalence on both sides. The Palestinians believe they are morally superior because more of them have died, and the Israelis believe they are morally superior because of their developed political culture as well as the conviction that they are a legitimately established state that is surrounded by enemies and simply defending themselves.

Research on political cartoons reports that cartoonists want to expose the system and encourage resistance. They clearly have an agenda, which is fine because that’s their job. But a persistent bias toward one issue is no different than any journalist engaging in conscious and systematic bias with respect to an issue. An editorial cartoonist is particularly adept at exposing hypocrisy and absurdity and these cartoon moments are powerful when there is a consensus recognizing hypocrisy and absurdity. But a cartoonist who simply hammers away portraying his or her own biased political perspective is little more than a journalist hack.

Political cartoons are naturally critical and typically have a sharp cutting-edge humor and insight to them. And this is why we enjoy them. If they subvert those in power and draw attention to the corruption of deep or sacred principles than editorial cartoons are powerful communication forces. A cartoon may not prompt revolution in the streets but it can be and should be oppositional in the most honorable sense. If we laugh or see ourselves in bitter recognition then the cartoon is successful. But propagating an indefensible cultural stereotype aimed at one culture and interpreting that culture through a single lens (the accusation of Israeli moral superiority in this case) moves beyond insightful cartoons into the realm of rank bias.

What Kind of Mentality Kills Teenagers Because They are Jewish or Palestinian? I’ll Tell You What Kind.

You have to be pretty far outside the category of “human” to kidnap three scared teenagers and shoot them in the back of a car. Shoot them for no reason other than they fit the category of “other.” The murder of Naftali Frenkel and Gilad Shaar, both 16, and Eyal Yifrach 19, and the Palestinian Mohamed Abu Khdeir reveals the monstrosity that can arouse itself in humans whenever group membership is highly salient and fueled by powerful beliefs such as religion. Let me explain how framing a conflict can be murderous.

Experts talking to lay people usually make the point that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not about religion or culture but land and national rights. It is a conflict between national political movements – Zionism and Palestinian nationalism – and perhaps includes broader Arab nationalism. Framing the conflict this way is actually quite good and beneficial. In addition to the practical implications, describing the conflict as one between two national political movements makes the conflict more amenable to management and resolution with all of the attendant rational and political bargaining. It implies sensible trade-offs and compromise along with future relationships and the positive attitudes and beliefs that will accompany these compromises and future relationships. Each side will broaden its circle of humanity and slowly include more of the other.

But with the integration and the unity government formed between Hamas and Fatah, not to mention the Hamas Charter and its aggressive religious history, we have a powerful religious element introduced. Islamizing the conflict is our worst nightmare and begins from the simple category definition of the conflict as one between two rival religions Islam and Judaism. Or, to put it in even more intractable terms, a conflict between two opposing absolutes. Now attitudes about the other are not subject to rational trade-offs and the anticipation of future relationships. And yes, the conflict can be Judiazed but there are important differences which we will take up at another time. This post is mostly about Islamizing the conflict. I will deal with revenge later.

Turning the conflict into a religious one between Islam and Judaism means you operate with only two categories – the ingroup and the outgroup with all of the biases and mental distortions that demonize and dehumanize the outgroup and wildly exaggerate the truth of the ingroup.

The murderers of these teenagers did not see human beings, they did not see naïve young boys, and they certainly did not see three individuals who like sports, school, and their friends. No, they saw three Jews or a Palestinian who are all alike; they saw the “other” who was responsible for usurping the holy land; they saw grossly distorted historical monsters who – as the Hamas Charter indicates – were a demonic force on earth, bloodsuckers and the killers of prophets.

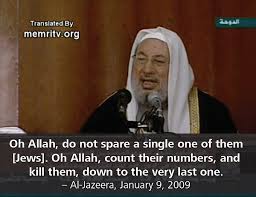

And it’s getting worse. As Hamas asserts itself Judaism becomes its primary enemy. The hate and narrowing categories of acceptance will reach hallucinogenic proportions as Jews are described in demonic terms and according to the Hamas Charter are a “corruption on earth.” It will be increasingly easier to kill innocent teenagers because Islamizing the conflict drained them of any remnant of humanity.

The Hamas Charter – and I encourage everyone to read it to fully appreciate the depths of its depravity – relies on the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. The old charges of the Jews controlling everything would be laughable if they were not so consequential. Hamas is not bargaining over land because Palestine is sacred and not subject to division or occupation by anyone else. There will be no discussion of borders, or settlements, or land swaps. Palestine is dar al-Islam (the abode of Islam).

Islamizing the conflict is the worst thing that can happen from a contemporary social science and intergroup conflict point of view. It will increase the distance and differences, and decrease opportunities for positive contact even more than they are. As the two groups retreat into their own worlds and formulate their psychological and communicative categories such formulations will be increasingly based on misinformation, distortions, historical inaccuracies, stereotypes, and emotions until the two groups retreat to their respective corners each having drained the other of even the slightest consideration. At that point it becomes easy to murder teenagers.

Evidence-Based Thinking is Necessary for Proper Deliberation

I have a sinking sense that schools don’t teach much “evidence-based thinking” anymore. They do teach critical thinking which is related but students are remarkably poor at defending propositions and recognizing thoughts and beliefs worth having. Although here is a blog site devoted to evidence-based thinking by two energetic young fellows. This spills over into the deliberative process because many citizens and political activists suffer from some of the same deficiencies. For some time now we have seen the diminution of the effects of Enlightenment thinking and science. From religious extremists to Tea Party members there’s plenty of anti-rationalist thinking and pseudo-intellectual discourse.

But things get worse. There is a clear disdain for logic and reasoning in some circles with many holding a toxic dependency on popular culture. This is not a particularly new phenomenon because Richard Hofstadter’s Anti-Intellectualism in American Life published in 1963 began to note the decline of the principled and evidentiary intellectual society and its replacement – the persuasion of single-minded people tenaciously holding onto a belief, opinion, or feeling and doing nothing but looking for support for that belief rather than its improvements, or accuracy, or truth value. I term this, the backside of evidence based thinking, confirmatory thinking in honor of the confirmation bias which is that people favor information that confirms what they already believe. But it gets worse. I count four ways that thinking is deficient because it is not evidence-based.

The difference between coincidence and causality is sometimes not completely clear but important to understand. Those who oppose vaccinations believe that all drugs have negative effects and any new vaccination would be the same thereby confirming their depreciated knowledge about medicine. They hold a mistrust of government and consequently any government program – even a highly evidence-based program that saves children’s lives – is rejected. A consistency of their own belief is more important than the evidence that supports the value of vaccinations.

A second sign of diminished capacity for evidence is simply how science and methods for making decisions work. The past and knowledge is strewn with failures and disappointments. Even when studies are unsuccessful and wrongheaded they make for a certain amount of information that is still of scientific value. It is comparable to the quip attributed to Edison that after he failed 200 times to make a light bulb he was not frustrated because he learned 200 ways not to make a light bulb. Evidence-based thinking requires developmental and evolutionary attitudes towards the unfolding of better and more precise information. Even though information can be wrong and lead you down wasteful paths, these paths are part of the process.

Basic misunderstanding of the logic of research is also a third issue. I’m not talking about standard logic or sophisticated mathematics but about basic principles of research and conclusions based on quantitative data. What it means for something to have a mean (average) and variation around the mean. Or, to have a sense of why and how numbers are influenced and change over time. This would include the logic of the experiment and the quality of conclusions when conditions are controlled and only a single experimental factor could have caused variation.

Lastly, one of the easiest ways to never get out of your own head and to hold fast to wrongheaded beliefs is to dispute, challenge, and dismiss those who are credible; in other words, to care more about maintaining your own consistency by rejecting experts and those more knowledgeable. We cannot all be experts on scientific and political matters so we must often rely on the expertise of others. And even though challenging and checking on the credentials of others to ensure source reliability is an important critical stance, this is not the same as knee-jerk rejection of experts. It seems as if those on the conservative end of the spectrum are quick to label all sorts of science as biased against the environment, or the climate, or finance because they inherently mistrust the source of any information and easily gravitate toward rejecting inconsistency with their own ideas then truly exploring and integrating new information.

There are all sorts of ways to distort information or disengage from it. And even the most conscientious thinker allows biases to creep in. But the attitude and willingness to engage, integrate new information on the basis of sound evidentiary principles, and change as a result of this evidence is what makes for more rigorous thinking.

Jihadists Humiliate Us: What Can We Do

I had a good chuckle the other day at the story of the Iraqi insurgents who captured the city of Mosul and found five nice American-made helicopters. They noted that the helicopters were pretty new and said in a posting on Twitter, “We expect the Americans to honor the warranty for these helicopters and service them for us.” Apparently even one of the most brutal jihadist groups has a sense of humor. But there is more than a prideful display of humor here. The comment was meant to humiliate. Even though it is a rather benign attempt at humiliation, and aimed at a strong target, it meets the conditions of humiliation as a communicative act between groups engaged in intergroup conflict.

Humiliation is an attempt to subjugate or diminish the pride and dignity of the other. Moreover the recipient of the humiliation is forced to feel helpless and if the humiliation is potent and long-lasting it can have deep psychological effects. Traditional societies rely on a sense of order and hierarchy and keeping the lower ranks “down” is expected. But when someone of status or higher rank is humiliated it is especially unacceptable because it does not serve the social order of the group, and it is especially painful for the higher status recipient. Acts of revenge and retribution are common. Jealousy, which is a powerful jailhouse emotion, is rooted in humiliation and the sense of being rejected, inferior, and disrespected. You can read a little more here.

Violence is especially likely when a formerly humiliated group feels powerful enough to humiliate its former tormentor. That many Middle Eastern Arabs and Muslims feel humiliated by the West is commonly enough understood. But now that the formerly subjugated are in positions of power – or at least are feeling powerful – they will return the humiliation. Considerable historical violence (Hitler, Osama bin Laden, Rwanda, South Africa, colonial violence) is associated with humiliation. Moreover, trauma and victimhood are intertwined with humiliation in some complex ways. Anger, rage, and antagonism are strongly associated with political conflict and violence and very dangerous when associated with humiliation.

So what are we to think of our jihadist friends and their gleeful humiliation of the United States? We can ignore it which is often a good strategy and consistent with the popular ideology that says “nobody can humiliate you unless you let them.” This is not a platitude I consider very effective but it is the case that I have some control over how I feel. This little slight humiliation is insignificant enough such that ignoring it is easy. There is always dialogue and reconciliation and attempts to reconstruct relationships such that humiliation is not part of the new relationship. This is ideal and desirable, but difficult.

These jihadists fellows are feeling their oats with respect to military victories and this effort to exercise autonomy and stand up to the humiliater make for feelings of joyful catharsis. But if they were serious about problem-solving of any type they would take the next step which is to transition to a more balanced and respectful relationship. Former underlings who change their own consciousness first are in a position to change the other.

Then again, all of this is laughably idealistic as we read about the savagery of these ISIS (Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) groups who casually execute prisoners, behead rivals, and loot the communities they conquer. On second thought, a little humiliation does not sound so bad.

The Paralysis of Choice

Ever since Kahneman and Tversky’s groundbreaking work we have accepted the fact that humans just aren’t very good at choices and keeping the best interest of everyone in mind. We believe our thinking and decision-making processes are clear and logical when in fact we are inconsistent in many ways. I presume most readers of this blog are familiar with this general pattern and I will not elaborate on it except to say that we make many types of mistakes: we exaggerate what we know; we overvalue some objects for illogical psychological reasons; quality information sometimes does not matter; we shift choices for ideological reasons; we unconsciously seek out confirming information; on the average, humans are more unreflective, impulsive, and subject to illogical influences than we are “rational.” A recent article in The Nation captures these issues.

But those of us interested in deliberation, political communication, group decision-making, and group processes cannot easily abandon the issue of choice or making decisions. We cannot simply throw up our hands and say “people are irrational.” We must continue to explore these matters and find ways to improve.

For starters, we should confront our historical ideology about the value of choice. As a liberal democracy and market economy we naturally believe that choice is better, and the more choices you have the freer the market and the richer the environment. But some who have written about this issue demonstrate how we are constantly anxious and unsure of ourselves because of so many choices. We are constantly in the state of insecurity and questioning whether or not we have done the right thing whether it is a choice of a school, a food item in the market, a financial plan, or any number of other choices.

Still, one of the most interesting and creative ways to think about choice is the role it plays in a democratic society. In other words, choice can be related to political ideology such as those choices explained in Gladwell’s The Art of Choosing or Ben-Porath in Tough Choices. One political argument for the role of government is that it levels the playing field; when the distribution of money and resources becomes unequal government steps in and constrains choice markets. Clearly we do not make choices in a perfectly rational market – some members of that market have fewer choices than others and of less quality – so a middle force such as a government steps in and levels the playing field choices.

Again, part of this intervention is “behavioral economics” where the state or a business manipulates the environment so you will make certain choices. For example, automatically transfer a portion of payroll to a savings account and require the individual to “opt out” rather than “opt in” which increases the statistical likelihood of saving.

No, those of us interested in the communication process, the deliberation process is epistemic; that is, communication can produce new knowledge and new possibilities. Difficult problem solving is not simply a matter of choosing a correct choice that is more rational than another, or selecting an option that has maximized value. Much of this work in “choice” and the processes that influence choices is less relevant to deliberative theorists. Deliberative communication emerges from the literature on deliberative democracy and is rooted in the advantages that accrue from reciprocity. “The basic premise of reciprocity is that participants owe one another justifications for their institutions, laws, and public policies that collectively bind them.” This means that justice and the legitimate acceptance of social and political constraints on a group must emerge from a process where all parties have had ample opportunity to engage in mutual reason-giving. From reciprocity flows respect for the other. Scholars also refer to publicity and accountability as essential conditions of deliberative democracy. That is, discussion and decision making must be public to ensure justifiability, and that those who make decisions on behalf of others must be accountable. Binding decisions lose moral legitimacy to the extent that they have been made in a manner unavailable to the public, or by individuals who are not accountable to their constituencies.

What is particularly important about deliberation from a communication perspective is its ability to transform the perspective of the individual. Election-centered and direct democratic processes value the individual, but focus primarily on the opportunity to participate. Deliberative processes draw on communication in the form of discussion and argument with the aim to change the motivations and opinions of individuals. The deliberative process contributes to a changing sense of self and identity because participants are immersed in a social system that manufactures new ways to think about problems and orient toward others. This deliberative social system moves people out of their parochial interests and contributes to a broader sense of community mindedness, as well as providing new information that clarifies and informs opinions. The issues pertinent to categorical choices are relatively inconsequential to deliberation.

Unleashing the Blogs of War

The blogging community is growing, stretching its muscles and increasing its influence. Blogs are, according to a number of studies, providing more insight and more thoughtful analysis than traditional media. Clearly, there are amateurish and ineffectual blogs that contaminate the blogo sphere but these will always be with us as long as communication environments are unrestrained.

In a study by Johnson and Kaye (Media, War & Conflict, Vol 3, 2010) they discovered that the Iraqi war was a significant event with respect to blogs when people began to see them as more thoughtful and often more accurate than traditional media. Until then, blogs were mostly annoying sideshows dismissed by quality journalism as something not to be taken seriously. But soldiers in Iraq who began to write war blogs and report on what they were seeing, including a natural view of the military and the culture of military life, began to acquire support. These military blogs were popular and attracted the attention of traditionally trained journalists as well as the public.

But a strong majority of Americans who supported the war up until the toppling of Saddam Hussein began to fade away as the war effort shifted to state building in Iraq. Attention to blogs began to wane and it appeared that military blogs were consistently the most popular and blogs lost some of their appeal as things moved to routine politics. Still, the public recognizes that government sources control wartime news and these sources of course have their limitations and biases. The beginning of the Iraqi war and the hunt for Saddam Hussein produced more cheerleaders than journalists.

In time of war blogs written by soldiers are particularly popular for some rather straightforward reasons. They offer up more detail, insight, and perspective as well as assumed to be more authentic. Moreover blogs by soldiers, or more detached participants, can write in a subjective and breezy style that does not adhere to normal journalistic standards. And although this can have disadvantages it makes for more enjoyable reading. The interactive features of blogs are also very popular where readers can respond and initiate extended discussions.

Johnson and Kaye found that blogs were influential in establishing perceptions and had the power to influence opinions. Readers of blogs in their study reported increased influence and attributions of credibility about the blog as time went on. There are of course a number of political and foreign-policy explanations for this including the influence of changing popularity from traditional media.

Also of interest is the predominance of Republican and conservative ideology among blog readers and users. We would expect military blogs to be largely conservative but overall blog attention increases among Republicans and conservatives. In the same way that conservative radio and television is more popular or “works better” than liberal programming, conservative ideologies seem to seek out alternative media probably because of their general belief in liberal media bias.

Some years ago it seemed quite unlikely that citizens would drift away from CNN and traditional news and start partaking regularly of blogs for war news, a time when blogs were considered more hardscrabble upstarts then respected and reliable. But the blogosphere is growing and shaping itself into something significant as well as genuinely challenging traditional news. The blogs of war were unleashed during the Iraqi war just at the moment where technology and politics intersected.

News from the Palestine Papers: Wikileaks and Media Foreign Policy

Four years ago in 2010 Al Jazeera acquired a set of documents known as “The Palestine Papers.” These were classified documents characterizing behind the scenes comments pertaining to the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations as far back as the Madrid conference and the Oslo agreements in the early 1990s. They included emails, minutes, transcripts, reports, strategy papers, and draft agreements all detailing the US mediated negotiations. The Palestine papers can be accessed in English at this site: The Palestine papers. Moreover, a more detailed analysis of the Palestine papers and the issues discussed below appears in Zayani (2013) in the journal Media, War & Conflict.

Of course, the release of these documents can be and was hailed as a blow for freedom of information, greater exposure to the truth, and a gold mine for scholars. Al Jazeera began by holding the documents closely but then found it too overwhelming to deal with and decided to make them available on a website for all to examine. But what is the main news value of these documents? What information is truly relevant and informative? It was tantalizing to read some memos and examine what were thought to be private opinions, but what are the real political effects?

It turns out that the release of these documents was pretty damaging and just possibly might have set the entire negotiation process back. They are a good example of how media can reorganize relationships can cause changes in the issues. We can see this with respect to issues if we compare the state of negotiations in 2010 to the present. First, in 2010 the Palestinian Authority was trying hard to keep Hamas out of the picture. The Palestinian Authority was trying to minimize Hamas and establish themselves as the dominant Palestinian political unit. This was the preference of the United States and Israel each of which assumed that negotiations would be more middle ground and mainstream without Hamas. There was even documentation representing a covert operation between the Israelis and the Palestinian Authority against Hamas and cooperation between the US, Israel, and the Mubarak regime.

The Palestinian Authority was under critical scrutiny and embarrassed by the state of affairs. There were additional revelations about the weak performance of the Palestinian negotiating team and the strength of the Israelis including Palestinian concessions that made them look like they were outmatched by the Israelis and the United States. The Palestinian community felt their pride was eroded and even perhaps their leadership was in an unhealthy collaboration with Israel.

The exposure of these issues has had the effect of hardening the Palestinian position and essentially made negotiations more difficult. The recent formation of a unity government between the Palestinian Authority and Hamas is probably in some way a response to the WikiLeaks documents. Behind the scenes the Palestinians were seeking to marginalize a more extreme group, but the presence of new media that exposes these behind-the-scenes strategies put the Palestinian negotiating team in the untenable position. They have incorporated Hamas into the negotiations, and even though as I argued in an earlier post this might have some salutary effect, it is also possible that it will push the Palestinian Authority into more hardened and extreme positions.

Al Jazeera played an important role in the release of these documents. Some accuse them of making a conscious attempt to embarrass the Palestinians and empowering Hamas. The documents reconfigured the relationship between the Palestinians and other Arab groups by taking backstage behavior and pushing it to the front stage thereby redefining everyone’s role. But then again, this is what media does.

Striving for “Collective Reasoning”

Consider the example below from Sunstein of “incompletely theorized agreement.” Incompletely theorized agreement is when two groups in disagreement agree on the preferred outcome but disagree on a more general theoretical rationale. A deeply religious Christian and a scientist might both want to protect a living species from extinction and work together to accomplish that but for different reasons. The Christian may be motivated by the belief that the species is part of God’s grace, and the scientist justifies his preferences on the basis of a balanced ecological system. The solution is incompletely theorized because they agree on the most practical problem solving level but disagree at a deeper theoretical rationale. Israelis and Palestinians disagree on a deeper fundamental level. An Israeli Jew might believe the land was bequeathed to them in the Bible and they are doing little more than returning to a historic homeland. A Palestinian would hold that the Jews were colonialist in their domination of the land, and that the Arabs are the indigenous population. The goal is not to battle it out trying to change the mind of the other on such fundamental issues, but to move to a different more practical level of cooperation that is shared by the participants rather than focusing on the theoretical rationales that divide them so. This is collective reasoning.

You have heard the quip “come let us reason together.” Well, it is possible to reason together and during quality deliberation it is termed “collective reasoning.” It is primarily concerned with what is termed “rational cooperation” with particular emphasis on conflicts between divided groups. Collective rationality involves more than decisions about desirable outcomes that benefit only an individual’s judgment about value. For example, if everyone in a community contributes a small amount of money to improve the road in their community and incurs an individual cost, but a collective benefit (improved roads in the community), then this is a decision based on collective rationality. It is sensible for the whole group to accept such a decision. Of course the individual cost can be too high for some or repugnant to others, and there can be debate about the actual cost and required contribution, but this entire process still represents a form of collective rationality. A decision to contribute in this example is not governed by pure individual rationality otherwise an individual might decide to free ride or not contribute at all.

Part of the power of deliberation is its reliance on collective reasoning which is mutually beneficial cooperation. This prompts the question if collective reasoning is based on mutually beneficial cooperation then the deliberative theorists must ask how do we produce this cooperation, and how do people benefit from it? The communication patterns and social conditions that move people from their individual rationality to collective rationality are also of considerable interest. Most people begin a conflict with a clash of individual perspectives, narratives, and data. The first impulse is to conclude that one’s own choices are best for him or her and then go about the individually rationalistic process of trying to maximize your own rewards and not deviating from these efforts. It is only when groups continuously fail, or when they are experiencing a hurting stalemate, that they begin to shift their thinking toward cooperation rather than conflict. At some point when the efforts at resolution get serious, or when the likelihood of failure and loss increase, participants in conflict begin to reason seriously and collectively. But if deliberation is assumed at one point to be worthy, and not only for its democratic proclivities, but for its epistemic possibilities then cooperation in tasks such as gathering information, challenging interpretations, and making inferences is germane.

Collective reasoning is a communicative exchange designed to manage a problem. It is distinct from conversation in that collective reasoning seeks to answer questions and solve problems and is a more structured form of social contact. It includes justified judgment which is a conclusion or decision supported by relevant information and reasoning. To be a little more specific, collective reasoning expects the participants to acquire a justified judgment that would be superior to their individual reasoning. This superiority includes the benefits of cooperation; in other words, the collectively justified judgment may not meet all the desires of an individual but it satisfies them sufficiently as well as others. By way of illustration, if everyone in a group had the same information and made the same judgments about it then there would be simple agreement and deliberation to solve problems would be unnecessary. But if the group is characterized by unjustified judgments, and the accompanying tensions and disagreements, then they must expose themselves to some exogenous input – new information contact with someone outside their group experiences that can contribute to additional collective reasoning. This is conceptually similar to Simons’ problem of bounded rationality which is that individuals cannot go beyond the boundaries of their own abilities and knowledge. Deliberation and collective reasoning improves the availability of information and allows for the cooperative advantages that come from deliberative discussion. Even if someone else has inappropriate, inaccurate, or manipulative information such conditions can still sharpen my own considerations and potentially lead to new ways of solving problems.

What Do Condi Rice, Jean Kirkpatrick, J Street, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali Have in Common?

Here is a simple quiz for you: What do and J St., Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Jean Kirkpatrick, Condi Rice all have in common? Give up? The answer is all of them have been excluded, disinvited, and prevented from speaking just because they disagree with someone else. They have suffered from a political ideology and a form of political correctness in the worst sense of the word considered to be so fundamental on the part of some that deviation from that ideology amounts to heresy. Hirsi Ali is a passionate and committed human rights advocate who pays special attention to the rights of women. She was disinvited from speaking at Brandeis University because some thought she was too offensive to Islam. The same fate awaited Jean Kirkpatrick and Condi Rice two people who are little more than a slight verbal threat, but maintain clear political positions, to only those who disagree with them. The conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations has excluded J Street from their organization on the basis of a description of J Street as “out of step with mainstream Judaism.” In other words, J Street is too liberal.

Here is a simple quiz for you: What do and J St., Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Jean Kirkpatrick, Condi Rice all have in common? Give up? The answer is all of them have been excluded, disinvited, and prevented from speaking just because they disagree with someone else. They have suffered from a political ideology and a form of political correctness in the worst sense of the word considered to be so fundamental on the part of some that deviation from that ideology amounts to heresy. Hirsi Ali is a passionate and committed human rights advocate who pays special attention to the rights of women. She was disinvited from speaking at Brandeis University because some thought she was too offensive to Islam. The same fate awaited Jean Kirkpatrick and Condi Rice two people who are little more than a slight verbal threat, but maintain clear political positions, to only those who disagree with them. The conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations has excluded J Street from their organization on the basis of a description of J Street as “out of step with mainstream Judaism.” In other words, J Street is too liberal.

Leon Wieseltier’s article on J Street in The New Republic is an excellent critique of the decision by Major Jewish Organizations to deny J Street cover under their umbrella. Ruth Wisse of Harvard wrote about the closing of the academic mind in the Wall Street Journal because anyone who makes a slightly controversial statement must be vetted for ideological purity, to ensure that someone is not offended, before they can be an acceptable speaking candidate.

I grant you that civility and inclusion sometimes clash. There is a line, and I cannot define it but I know it when I see it, where including someone in the communicative process is counterproductive because their behavior or political positions are so odious as to be more destructive than constructive. But this is a decision that should be the exception rather than the rule. We must error on the side of inclusion.

The arguments and analysis pertaining to this issue are powerful and fundamental to American democratic principles as well as political theory. Inclusion is crucial if any sort of communication is going to achieve political legitimacy. Anyone potentially influenced by a decision has a right to be part of the influence process that determines the outcome.

And, as has been well established, listening to those with whom we disagree and exposure to the other side improves the quality of thinking and decision-making. Being inclusive increases the chances of moving from individual to more general appeals. A decision even if you disagree with it will be more acceptable and legitimate if it is arrived at through an inclusive process. The decisions to rebuff J Street for admission to a collection of Jewish organizations, to deny Ayaan Hirsi Ali the right to speak critically of treatment of women in Islam, and to shun Condi Rice and Jean Kirkpatrick because of their conservative values or association with some foreign-policy decision do little more than impoverished the marketplace of ideas.

Thomas Edison’s well-known quote applies equally to political rhetoric and the pool of arguments seeking consensus around an issue. Edison said the 2000 times he tried to make a light bulb were not a failure, he just learned 2000 ways not to make a light bulb. By listening to someone with a political position such as Kirkpatrick or Hirsi Ali or the position of J Street you are not diminished but enriched by exposure to the larger pool of arguments that will ultimately lead to improved understanding, or consensus, or whatever the rhetorical goal. Even the requirement of pluralism requires the ascent of citizens and for political positions to be reached by “public interest” and not the private beliefs of a few.

Managing Ethnic Conflict – Moscow Style

If we want to treat Moscow’s interventions into Eastern Ukraine and Crimea seriously for the moment we might ask about any legitimate concerns on the part of Moscow. But the issue of “legitimate” concerns that justify aggression against others conjures up the rhetorical history of the Soviet Union and their claim to have spheres of influence. Hitler and Stalin used phrases such as this to intervene in the business of others and claim their “legitimate” rights to land and military presence in order to protect Russian citizens or interests.

This is exactly the situation in Eastern Ukraine on the lands that border Russia. Even though these territories have culture contact with Russia and a history of political engagement, the current tensions are not so much the result of locals agitating for stronger associations with mother Russia but with interference by way of propaganda and Russian adventurism. Moreover, it continues Russia’s persistent attention to breakaway regions of the former Soviet Union. Russia has desperately tried to hold on to influence in some of the states (e.g. Georgia, Azerbaijan) but this typically backfires. Ukraine and Kiev will probably be even more oriented toward the West and Ukrainian nationalism will soar.

Ethnic Conflict without the Conflict

The old Soviet Union, like so many political actors, wore blinders that allowed them to see primarily the colors of ethnic groups. The Soviet Union divided and assigned groups to territorial units predominantly on the basis of ethnic heritage. Stalin in particular created ethnic territories and established a broad array of territorial units defined as states. These states were supposed to be homelands for particular national groups (Azeris, Armenians, Uzbeks, etc.). The strategy was to keep groups separate so they could not easily organize against Moscow. It worked for a long time until various groups began to demand independence. Soon, there was ethnic violence and Moscow had its excuse to maintain influence by stepping in and claiming to calm the situation.

Russia has felt quite comfortable intervening in the affairs of its former territories. Russia felt, in fact, very secure and justified by its movement into Crimea. About 58% of the population of Crimea is Russian so the claim to a sphere of influence has some standing. But if Russia feels as if some international commitment has been violated, then they should use diplomacy and the avenues available to them through international law.

The Basic Instruments of International Conflict Management

For my money, Russia has never been particularly good at managing ethnic conflict. Even though historically they oversaw with the old Soviet Union 15 Soviet socialist republics all of which had minority groups, Moscow is sort of a “bull in the china shop.” There are typically four intervention possibilities – military interventions, economic interventions, diplomacy, and dialogue – but Russia relies mostly on military options. In designing a macro level institution meant to facilitate ethnic conflict resolution, the Russians have never been very innovative or creative. Take the case of the Chechens for example. In the northern Caucasus of South Russia Chechens are increasingly a higher percentage of the population, and there are about 20% Russians. Even without Russia agreeing to Chechnya’s autonomy assuring fair treatment, increased cultural autonomy, and more political rights would be reasonable.

When it comes to designing macro structures for divided societies Russia seems to ignore all of them. First, an ethnic group must address the issue of territorial organization of the state. The Crimea, Eastern Ukraine, Chechnya and territories, Georgia, and other points of Russian interest are yet to resolve these territorial issues properly. Secondly, is the matter of the governmental relationship between the minority and the majority. And finally, Russia rarely concerns itself with the protection of identity groups and individual rights.

Putin may have successfully grabbed territory in the Crimea but he is increasingly competing with the West rather than a lesser prepared minority. And he may be banking on the fact that the EU will never consider Ukraine a proper European project, but this may be a dangerous wish as Ukraine increasingly turns its attention to the West and thereby makes progress on territoriality, sound governmental relations, and the protection of identity and minority groups.